Washington DC by Michael Reid OAM

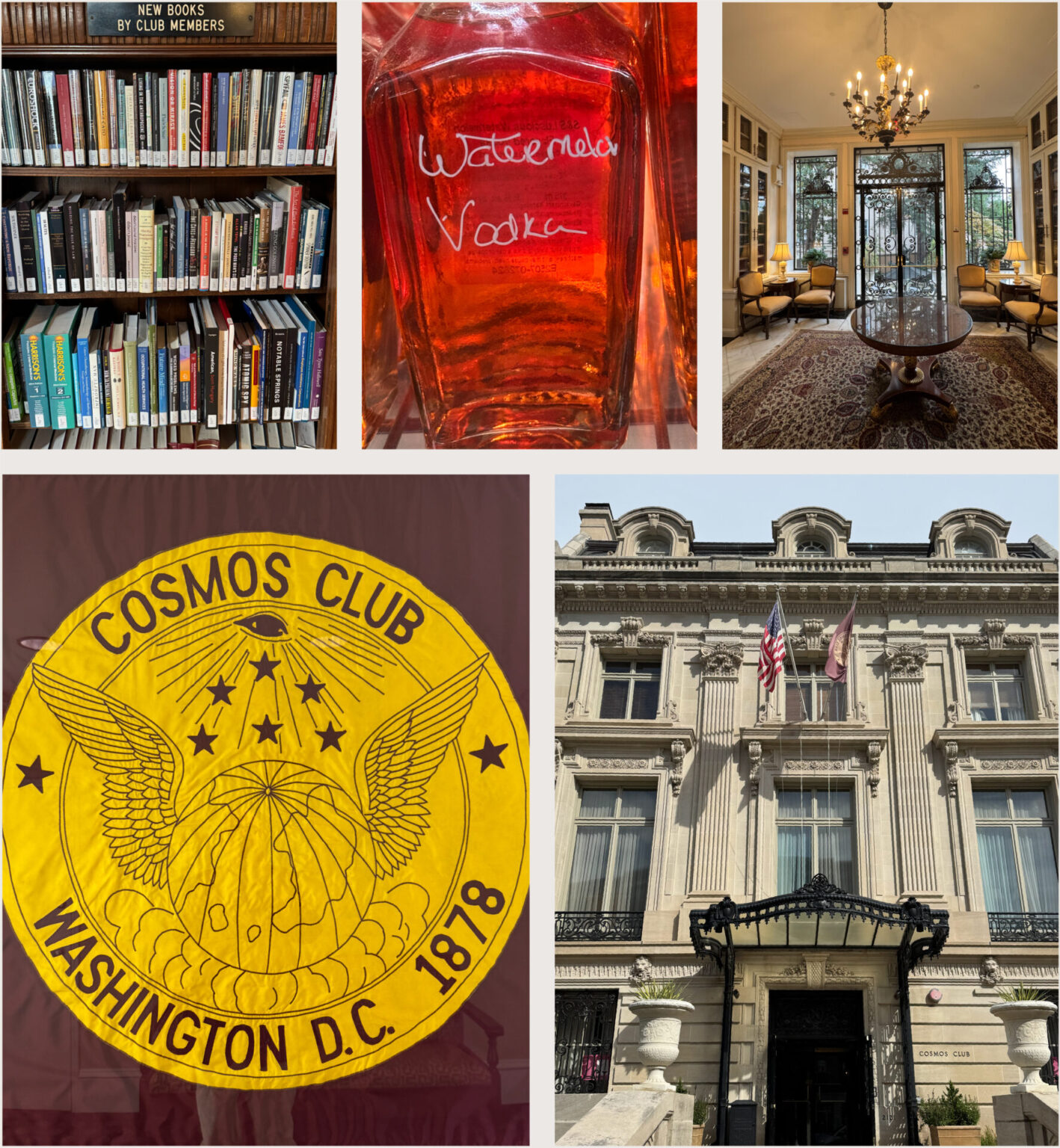

For the latest edition of The Murrurundi Argus, our chairman and director, Michael Reid OAM, reflects on his recent trip to the United States capital, where our expansive exhibition of contemporary Australian First Nations art, The Stars Before Us All, has extended its run to Sunday, 9 November, at our pop-up gallery in downtown DC.

There are, in Australia, buildings and individuals of considerable authority – but not so much of power. In the District of Columbia, or Washington DC, or simply DC as it is widely known, there are reminders – impressers – of real power. The whole Rome-on-the-Potomac thrusting projection of imperial majesty was no accident. From the uplifted, repurposed grandeur and legitimacy of the ancients, transferred – as the whole notion of Rome on the Potomac was – to a new world, to the image of a man of a certain age jogging early morning along the National Mall, flanked by close-quarters bodyguards whose presence quietly says Marines.

Washington pulses with dominance. The city hums to a constant wail of sirens – every decibel accounted for – with speeding motorcades, rotors, and roadblocks forming the soundtrack of authority on alert.

Power here feels physical — it moves, it breathes, it occupies space. In Australia, power tends to hide behind process and protocol. It’s softened by committees and smoothed over by a middle-class conformity we longingly refer to as egalitarian. In Washington, it wears running shoes and a security detail and jogs with some purpose down the long avenues of massive monuments – and carries a visible do-not-fuck-with-me vibe. In America, power performs. In Australia, it clears its throat.

Founded in 1790, DC was conceived by General George Washington – a reluctant revolutionary: disciplined, reserved, and driven more by duty than ambition, yet destined to embody the very idea of American power. Designed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the city was meant to express the ideals of the new republic, with grand avenues radiating from the Capitol and the White House.

The fledgling city struggled through its early years, plagued by swamps, disease and underdevelopment, before being devastated in 1814 when British troops invaded and burned the Capitol, the White House, and much of the city. Rebuilt and expanded, Washington grew into a fortified hub during the Civil War, symbolising the strength of the Union.

In the twentieth century, monumental architecture and national memorials transformed it into a showcase of American power – though racial and political tensions simmered beneath the surface. And still do. Following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson called in more than 13,000 federal troops to quell riots and restore order.

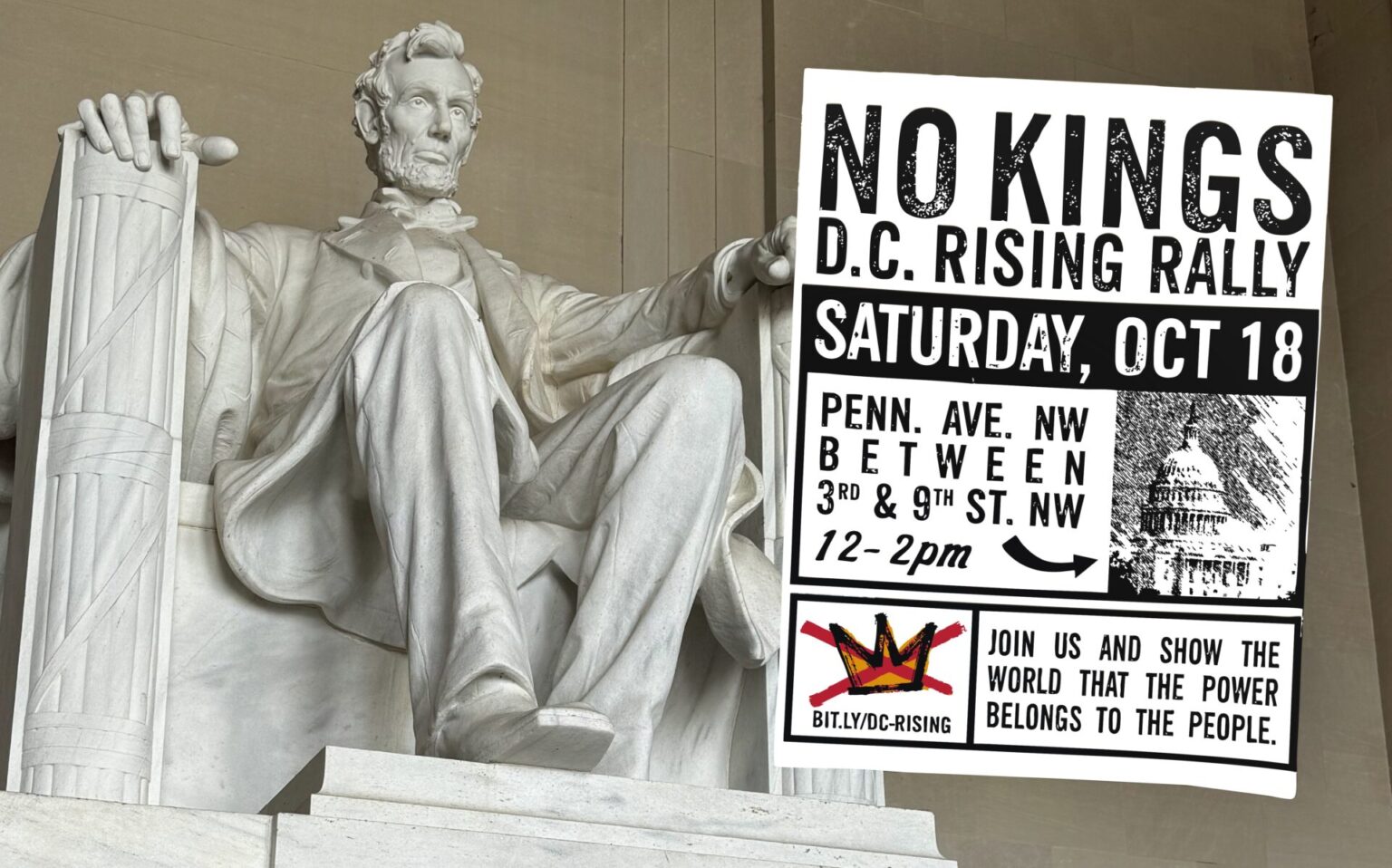

More than half a century later, in 2025, President Donald Trump again deployed National Guard troops to the capital – around 800 under federal control – declaring a public safety emergency and assuming command of the city’s police amid renewed civil unrest.

Unrest is the word du jour. During the ten days I was in DC, there was an ongoing federal government lockdown, the National Guard visibly out on the streets, and, on the day of our exhibition opening, the millions and millions who attended the No Kings rally.

This unrest is the result of a simple reality: America has become a deeply partisan place. Ever since Donald Trump’s second election in 2024, those once in the know have been forced to confront an uncomfortable truth – perhaps they did not understand America after all. The enlightened liberal class has been grappling with how to comprehend the rural and red-state Americans – those who live across the vast middle of the country, who feel that the economy, and the nation itself, have been passing them by, and who no longer see their lives or values reflected in the experience of the coasts.

The nation is now so divided that men broadcast their affiliations on their lapels. These badges help others know how to approach an upcoming conversation. In Washington, even civility comes forearmed. Once, a man’s sole jewellery signifier was his watch. A Rolex says this – solid, made it, successful. A Patek Philippe whispers – old money and deep wealth. In today’s America, alongside the watch, the lapel announces, before we have spoken, the institutions and organisations central to a man’s identity.

The American flag lapel pin is common. It says, “I am a patriot” – most likely more conservative than some, but the badge moves easily across divides. Then there are the all-important who-am-I badges.

On my first breakfast morning, I sat near two gentlemen – one with clear military bearing, speaking in a professional murmur, with phrases like “Russian sanctions” bubbling to the surface. These men wore a potpourri of badges, to the point of making a dandiest decorative-arts statement. The military man, notably, had a Ukrainian flag pin in the mix.

Around town, other lapel pins told their own stories. The Thin Blue Line flag pin – black and white with a single blue stripe – marked the law-enforcement fraternity. The Gold Star lapel button, a small gold star on a purple background, quietly signified a family’s loss in service. Veteran pins, round or shield-shaped with flags or unit crests, asserted experience and belonging. And then there were the practical laminated security badges – male and female – swinging from retractable cords that spoke even louder: in DC, access is the truest insignia of power.

As for the female insignias of affiliation, I have yet to decode them.

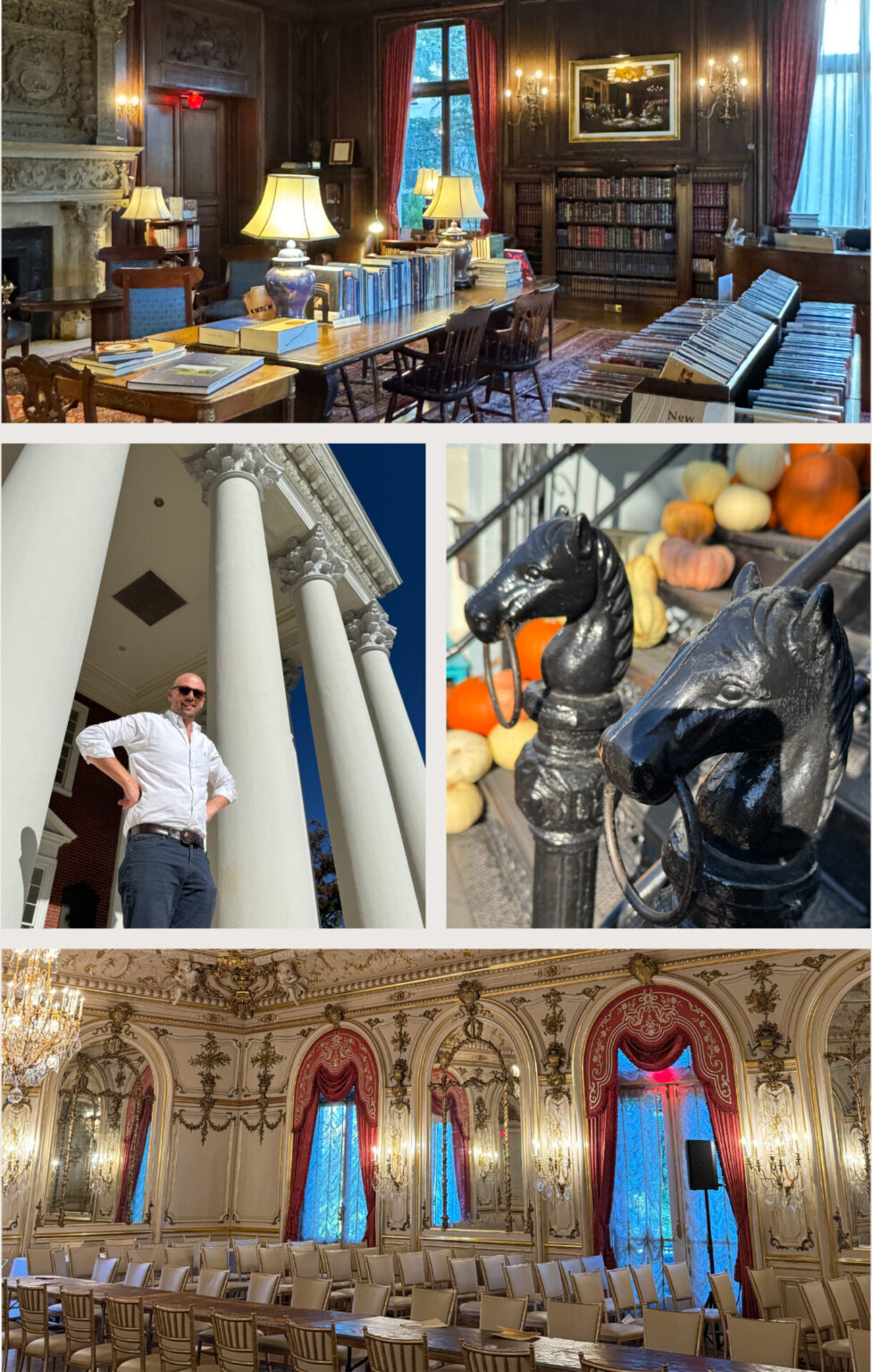

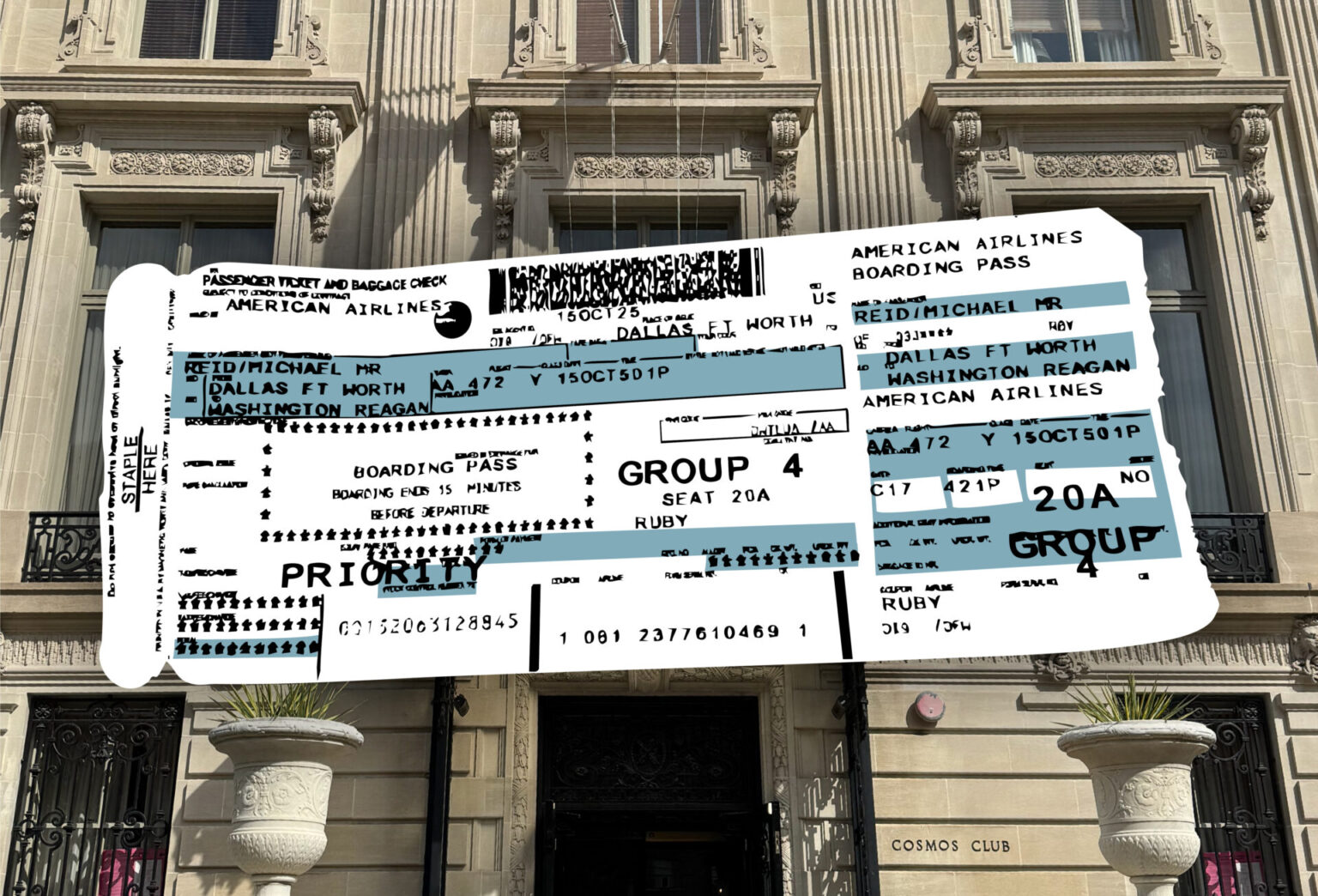

Amid this less-than-calm, my colleague and business partner, Director Toby Meagher, arrived in DC two days before my rather statelier business-class procession touched down. We were there for our month-long exhibition, The Stars Before Us All: Australian First Nations Art, held just a block from the White House. Why Washington? Because, in the footsteps of the good General George, we were shadowing the National Gallery of Victoria’s exhibition, The Stars We Do Not See: Australian Indigenous Art, originally scheduled to premiere at the National Gallery of Art on October 18, 2025 – postponed, as it happened, by a government shutdown. Our lights, however, went on exactly as planned.

We coordinated the Washington exhibition with another in Sydney. Artworks that were either too large or arrived too late for shipping to the US of A were shown in our Chippendale space. Toby and I had been working on this exhibition for a year. Artworks were sourced from Communities and private clients alike. The day before the DC opening, Toby rented a van and collected two paintings from a private client. The artworks quite literally came from everywhere.

The opening night drew a crowd of eighty to ninety. We were heavy on art museum curators and light on New York collectors. The private buyers had rescheduled after learning of the lockdown. The museum folk, already scheduled and paid to attend the opening of the National Gallery of Art, suddenly had space on their dance cards. A director of an extremely prestigious art museum – taking numerous photos of our exhibition – told me that had the shutdown not occurred, her program would have been too full to visit our exhibition. As it was, she had the time, and that, in itself, was important.

I estimate we lost between twenty and thirty private clients but gained ten to fifteen art museum curators – a loose lockdown dividend. Perhaps a silver lining. The Australian Financial Review ran a good, page-three, Saturday article on the opening – read the online edition here – and The Sydney Morning Herald also covered the show extensively – read here.

On the Monday of the second week, Regina and her niece Joy, nephews Hayden and Brett, Toby and I went by hired bus to the Kluge-Ruhe Museum at the University of Virginia.

Toby left DC the following Tuesday, and I was home alone with the exhibition for the next week. This would generally not be considered wise. Never one to be described as hands-on or practical, I had the keys to the front door – at least until the inevitable moment when I wouldn’t be able to find them. Anywho.

Home alone, the first thing I did was arrange a Zoom meeting with Shinola, the Detroit-based brand known for its watches, leather goods, and homewares. Of course I did. The meeting went extremely well. I learned that Shinola and Filson share the same private parent company — a fortunate connection, given our established partnership with Filson. Once they realised I already sell the Seattle-based outdoor woodsman brand in Australia, the conversation progressed swiftly and positively. We discussed an initial range of twelve watches and selected leather goods for Murrurundi, along with order minimums, display concepts, and logistics such as tax removal and shipping. In the coming weeks, I expect to finalise a dealership agreement making Murrurundi the exclusive Australian representative for Shinola. Bless.

Back to the DC exhibition. I did a number of early-morning private client walkthroughs that week, and my learning here is simple: if an individual requests an out-of-hours appointment, they acquire. Similarly, if visitors come during opening hours and then return, the likelihood of acquisition is far higher than for those who simply turn up for the drinks on opening night. On leaving, I had positioned six paintings to two collectors, from DC and New York. One of these collectors, the gallery had previously never dealt with.

As I head home, my colleague Daniel Soma, Head of Creative and Strategic Direction for the gallery, is coming over. We are extending the exhibition until 9 November, in the hope – and one would say some considerable hope – of being around when the National Gallery of Art in Washington reopens. Fingers crossed. So far so good.

Michael Reid OAM

- XXXVIII LA Story by Michael Reid OAM April 2024

- XLIX Paddy’s Cottage November 2025

- XLVIII Washington DC by Michael Reid OAM November 2025

- XLVII The Outdoor Fireplace at Murrurundi by Michael Reid OAM October 2025

- XLVI Amelia Zander of Zander & Co. July 2025

- XLV Marlie Draught Horse Stud by Michael Sharp June 2025

- XLIV Trump Engulfed the Fires by Michael Reid OAM February 2025

- XLIII Newcastle by Jason Mowen October 2024

- XLII The Business of Gardening by Michael Reid OAM September 2024

- XLI Carly Le Cerf by Sarah Hetherington August 2024

- XL Pecora Dairy by Michael Sharp July 2024

- XXXIX Joseph McGlennon by Michael Reid OAM May 2024

- XXXVII Julz Beresford by Michael Sharp March 2024

- XXXVI Sydney Contemporary by Jason Mowen February 2024

- XXXV The US of A by Michael Reid OAM December 2023

- XXXIV Scone Grammar School’s principal Paul Smart by Victoria Carey November 2023

- XXXIII AgQuip by Jason Mowen October 2023

- XXXII Tinagroo Stock Horse’s Jill Macintyre by Victoria Carey September 2023

- XXXI The Old Gundy School House by Victoria Carey August 2023

- XXX Annette English by Victoria Carey July 2023

- XXIX The Ghan by Jason Mowen June 2023

- XXVIII All in the family: The Arnotts May 2023

- XXVII A Capital Plan by Jason Mowen March 2023

- XXVI Mandy Archibald March 2023

- XXV Paul West February 2023

- XXIV The Other Newcastle by Jason Mowen January 2023

- XXIII Mount Woolooma Glasshouse at Belltrees December 2022

- XXII Murrurundi to Matino: with Jason Mowen November 2022

- XXI James Stokes October 2022

- XX Adelaide Bragg September 2022

- XIX Tamara Dean August 2022

- XVIII Going home: Angus Street July 2022

- XVII Belltrees Public School June 2022

- XVI A Road Trip on the New England Highway May 2022

- XV David and Jennifer Bettington: from horses to houses April 2022

- XIV Denise Faulkner: Art of the Garden March 2022

- XIII Childhood memories: Willa Arantz February 2022

- XII Riding ahead: Giddiup January 2022

- XI Ingrid Weir’s rural life December 2021

- X Life by design: William Zuccon November 2021

- IX Life on the land: The Whites October 2021

- VIII Goonoo Goonoo Station September 2021

- VII Murrurundi: a garden playground August 2021

- VI Pat’s Kitchen July 2021

- V A creative life: Charlotte Drake-Brockman June 2021

- IV Magpie Gin May 2021

- III The Cottage, Scone April 2021

- II At home with Jason Mowen March 2021

- I A town that performs February 2021