For the latest edition of The Murrurundi Argus, Jason Mowen visits Paddy’s Cottage, an idyllic contemporary farm stay set within the original 1920s weatherboard home amid the rugged magnificence of Green Creek, 15 minutes’ drive from Murrurundi. “Surrounded by these hills and wonderful vistas, the true value of this place is in its beauty,” says James Street – grandson of the historic property’s original owner, Douglas Royse Lysaght – who now resides here with his wife, Felicity. “Jamie and I see ourselves as custodians of the land,” adds Felicity. “It takes a huge amount of effort, but we’re maintaining history, and this gives us much joy.”

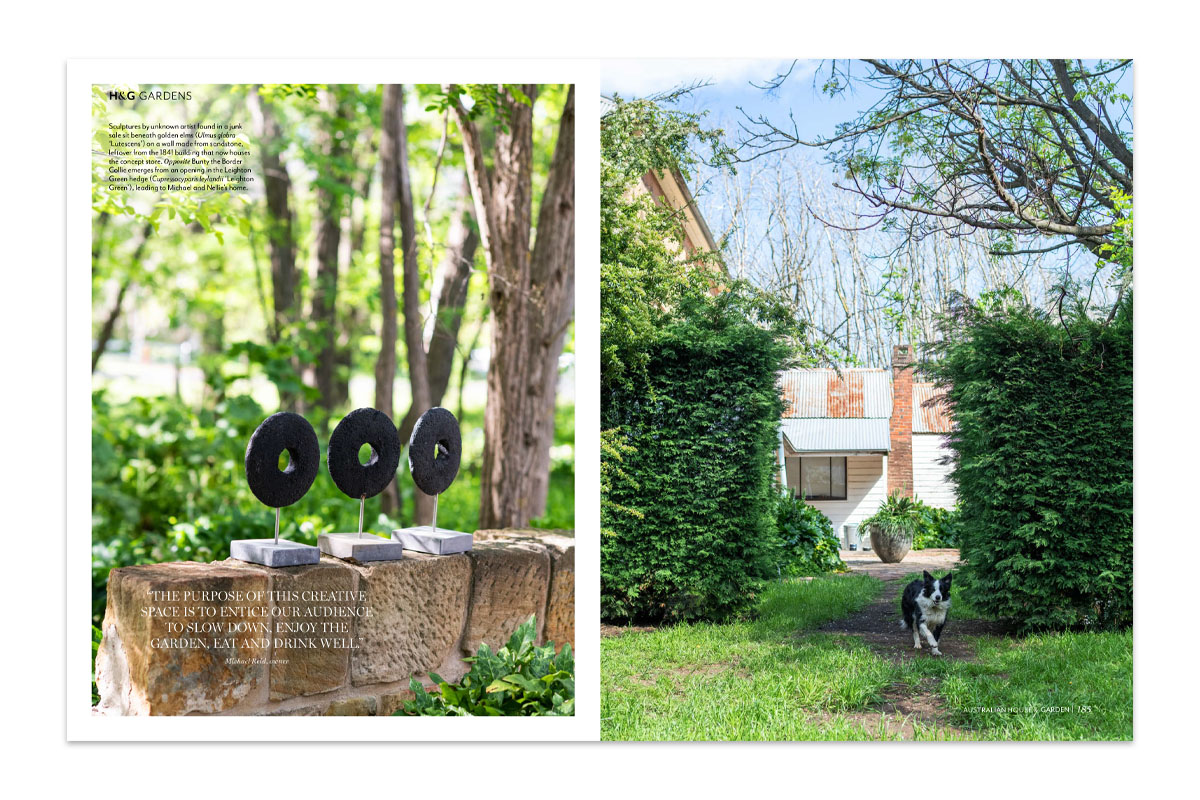

Of the scenic drives around Murrurundi, the one southeast of town through the neat paddocks of Emirates Park and out along the Timor Road is probably the most majestic. It slices through a wild, Brontë-esque landscape flanked by peaks, historic holdings and high-country vistas, leading to the homestead at Green Creek. Once there, over cattle grates and down a long and winding driveway, it’s hard to imagine a more Arcadian setting. At least the Australian version of Arcadia – rugged and magnificent.

Green Creek has long been a passion project. Herbert Lysaght bought the property, originally the lambing paddock of Harben Vale, as a project for his son, Douglas Royse Lysaght, in 1921. Today it is the home of Felicity and James Street – Royse’s grandson – with 2500 acres and a sprawling single-storey residence from the 1930s wrapped in colonnades and verandahs at the foot of Protection Hill. A gardener’s cottage, schoolhouse, meat house, dairy and tennis court sit among lawns and hundred-year-old trees, while the weatherboard cottage that had originally occupied the site was moved a short distance away, where it now overlooks the namesake creek.

Designed by Sydney architect Kenneth McConnel, the new Green Creek home was a big deal and went on to grace the cover of the 1947 tome, Planning the Australian Homestead. Its celebrity, though, was already long established – and not for its elegant design.

In September 1936, the project had reached lockup stage and James’s grandmother, Margery, was in Sydney selecting fabrics and furniture. On site, a plumber’s blowtorch came into contact with insulation under the eaves and the 26-room home, built chiefly of cypress pine, burnt to the ground.

“PALATIAL NEW HOME DESTROYED BY FIRE”, read one newspaper headline. “So sudden was the conflagration and intense the heat that the workmen who were camping in the building had not time to remove their belongings, and although there was an abundant water supply, nothing could be done to check the fire, and in half an hour the whole of the structure had been reduced to ashes.” Phoenix-like, the house was then rebuilt to the exact specifications. Sympathy goes out to “Mr. Smith of Newcastle”, the contractor who shouldered the cost.

Wanting to raise his family at Green Creek, Royse enjoyed these years of rural life, involved in the local community and particularly active in sporting clubs, playing rugby and co-founding the Murrurundi Golf Club. He was eventually called back to the family firm, Lysaght Steel. A stint in finance at Perpetual followed, later becoming chairman of CBC Bank.

“Green Creek was and still is one of the larger landholdings in the district but there are limitations in regard to the type of land use”, says James. “It’s hilly so not great sheep country, with issues around erosion; while it’s good basalt soil, it needs consistent rain. If you push it too hard, you’re the first into a drought and the last out. Today we have predominantly beef cattle, but surrounded by these hills and wonderful vistas, the true value of this place is in its beauty.”

James, his brother Matt and sisters Sarah and Hattie were raised at Green Creek, much like their mother, Helen Mary Lysaght, one of the four children of Royse and Margery. Felicity, meanwhile, hailed from a large sheep and cattle station near Quilpie in western Queensland before her family moved to central western New South Wales. “I grew up in the dry and arid environment of western Queensland and then at Mumblebone Stud, a property with significance in the wool industry,” says Felicity. “I really love Green Creek – it’s different to what I was used to but much like my father, Jamie and I see ourselves as custodians of the land. It takes a huge amount of effort but we’re maintaining history, and this gives us much joy.”

Which brings us back to the original weatherboard cottage. In the mid 1950s, Patrick ‘Paddy’ Brown came out from Ireland and worked on the construction of Glenbawn Dam, eventually settling in Murrurundi. He took a job as general hand at Green Creek for James’s father, Philip Street, and moved into the cottage, virtually untouched since its relocation in the 1930s. “There was a long drop, a copper boiler, a cast-iron bathtub in the kitchen, a smoking fireplace and not much else,” recalls James. “And Paddy loved it.”

After James commenced primary school in nearby Blandford, Paddy, who had been the welterweight champion back in Ireland, offered to teach him how to box. “A boxing bag was hung from a tree and each afternoon he would meet me straight off the school bus with a big old set of gloves. I was his little mate – we sparred and carried on and had a lot of fun.”

Having completed their studies, the just-married Jamie and Felicity worked in a nickel mine in the Meekatharra Desert in Western Australia and then spent a year travelling in Europe, before taking over the running of Green Creek in 1983. Their first son, Angus, was born the following year, followed by Simon and Amelia. “It was an idyllic place to raise three children and continues to be the heart of the family,” says Felicity. “We now have four grandchildren that also enjoy everything that Green Creek has to offer.”

Birds and possums were the cottage’s main residents after Paddy left in 1972. Many would have seen the structure demolished but Felicity and Jamie, realising its historical significance and potential as a farm stay, took the decision to restore the cottage in 2020, bringing it back to life over the course of a painstaking two-year renovation.

Today the simple, rustic luxury of Paddy’s Cottage (alongside three bedrooms there are two bathrooms, a proper cook’s kitchen and a charming mix of antiques and modern) stands as a far cry from the long drop and copper of Paddy’s era, although the beauty of the setting remains unchanged. Sitting on the verandah as the sun drops behind Protection Hill, throwing land and sky into a rainbow of colours, close your eyes and the affable Irishman’s presence is felt. Royse and Margery are there too, represented by their well-travelled collection of steamer trunks.

The original woolshed and shearer’s quarters from Royse’s time are visible from the verandah. It was there, in the late 1980s, that Felicity began hosting guests at Green Creek, after converting the shearer’s quarters into student accommodation. With two young children and a third on the way it wasn’t to last, although the experience laid the foundation for Paddy’s Cottage.

“Jamie and I feel incredibly privileged to have lived at Green Creek for the past 40 years and have always felt it had great tourism potential. Paddy’s Cottage is a part of that journey,” she says, “sharing the beauty of this country with our guests, and with the aim of leaving Green Creek in good stead for the next generation.”

@paddyscottage_greencreek