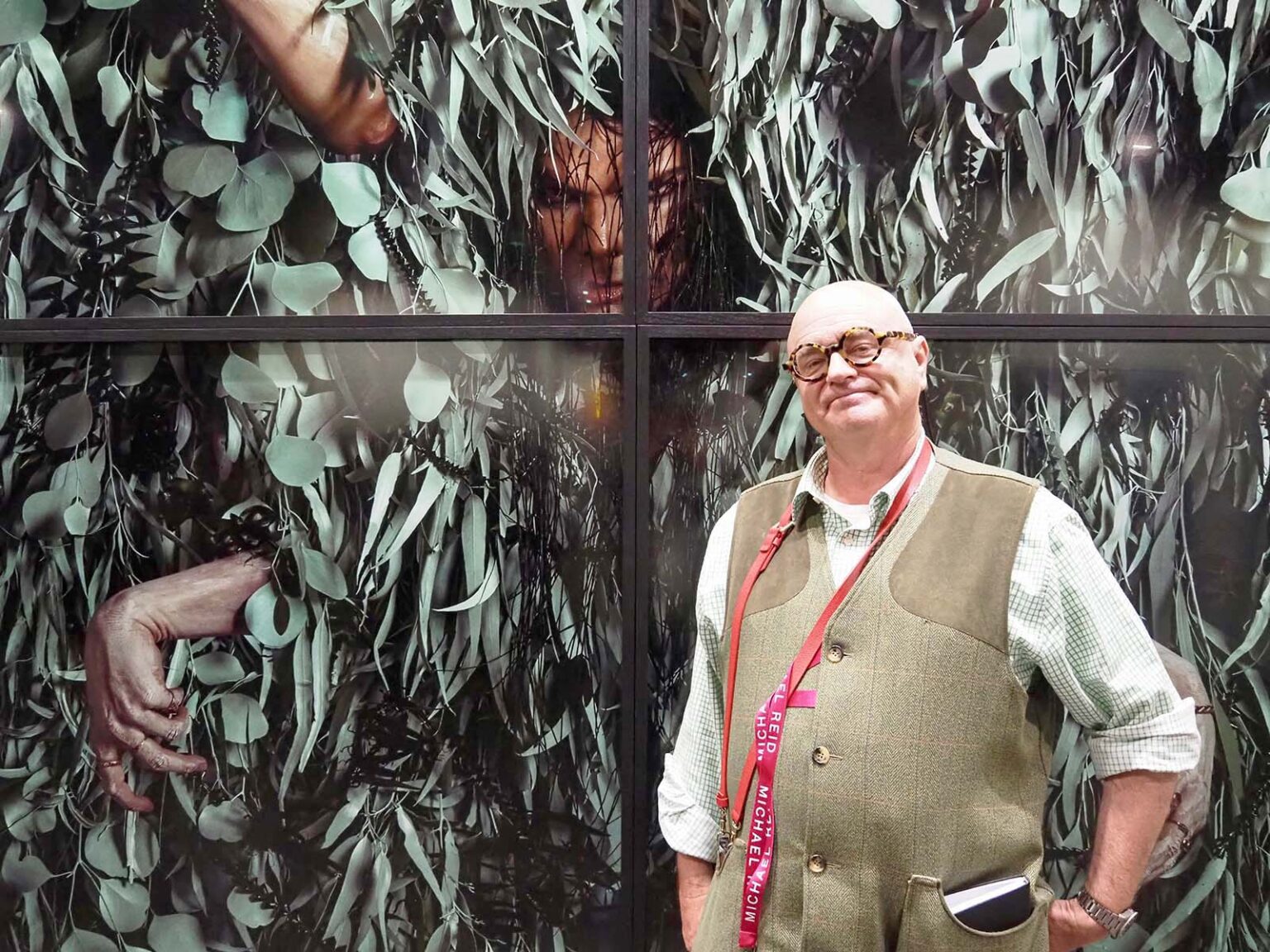

Scouting locations for an upcoming creative venture in Los Angeles, Michael Reid OAM returned to the Californian capital amid raging fires and an unsettling inauguration. Here, he reflects on this uneasy moment and the historical echoes of the American empire at a tipping point.

The week before landing in Los Angeles, I received several concerned texts inquiring as to whether I still intended to travel. Thank you, but of course, I was. Being that person and believing I’m in the know, you realise that the defining characteristic of the greater Los Angeles region – an area spanning 18 million people and over 53,000 square kilometres – is its vast, vast sprawl. While tens of thousands had been ruthlessly displaced by nature and were dealing with the immediate need for shelter, many other residents I spoke to grappled with the unsettling experience of witnessing an extraordinary crisis unfold from afar – but not that far. “They, like, live right next door, like, to the whole thing, like,” Almond Mulk latte, like, in hand, like. (The Mulk Co is a brand.)

Days after arriving, driving around Beverly Hills, I could see a glow to the north. Hotels were full of dogs. And then there was President Trump’s inauguration. The fires were briefly engulfed.

It took me several days to process everything and come to a settled opinion after the inauguration, simply because I felt so uneasy. It wasn’t unsettled in a value-judgment kind of way. I am not here to debate whether President Trump’s inauguration was right or wrong. The fact is that Trump was inaugurated as the 47th President of the United States of America. The American people voted, and Trump won – both the electoral vote and the popular vote. He also won, by a slim margin, in all the key swing states. The American people made their choice. It’s not my place to judge them or their decision.

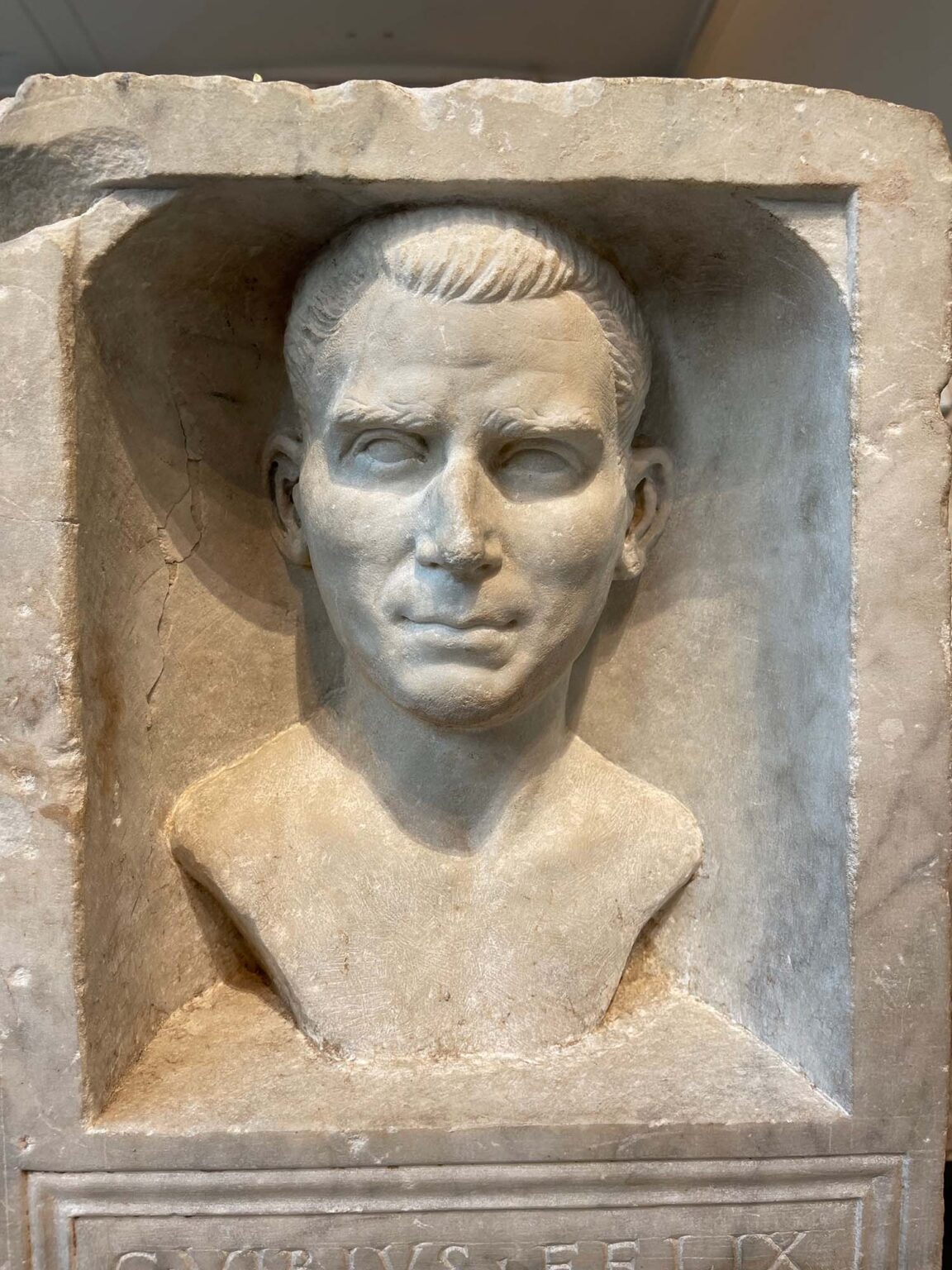

But I felt uneasy, and it took me a while to figure out why. I eventually realised that unease stemmed from my education under an incredibly rigorous and meticulous teacher, Mr. Lindsay Newnham. Mr. Newnham was my Ancient History teacher at Wesley College in Melbourne. Mr. Newnham heavily emphasised the writings of Thucydides and the history of the Peloponnesian Wars (431– 404 BC). This masterwork, authored by Thucydides – an Athenian historian and general – remains one of the earliest scholarly works on humanity.

As tangential as this stream of consciousness may seem, we studied, over many long and beautiful school days, why the two great city-states – Sparta, an autocratic state, and Athens, a democracy – went to war and why Athens, the democracy, ultimately lost big. One of Thucydides’ key insights was his belief that Athens’ democracy had morphed into an imperial, autocratic state. Its blunt authoritarianism and unconcerned self-centredness alienated its allies, causing them to abandon the Athenian cause. Left alone, Athens faced a warlike state in Sparta, which had the unwavering loyalty of its allies.

While Thucydides does not explicitly state a single quote summing up the necessity of alliances, his narrative repeatedly underscores the value and risks of alliances in securing power and resources during war. One notable excerpt reflects this theme: “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” This quote captures the harsh realities of power dynamics in alliances and conflicts. Offering up a teaching moment, Thucydides again and again illustrated that alliances were essential for both great and small states. For the great powers like Athens and Sparta, alliances provided additional military and economic strength. For smaller states, alliances offered protection against the predations of larger powers.

What I saw within President Trump’s 2.0 inauguration mirrored for me the Athenian slide from partnerships to domination. The rhetoric of “America First” evoked a sense of America standing alone. “The golden age of America begins right now. From this day forward, our country will flourish and be respected again all over the world,” and “We will no longer surrender this country or its people to the false song of globalism.” These statements reflect President Trump’s commitment to prioritising American interests, often advocating for a more unilateral approach in international affairs.

The unyielding emphasis on isolationism and disregard for alliances reminded me of Thucydides’ cautionary tale. History, as Mr. Newnham drilled into us, shows that great powers are made great because of their alliances. The breakdown of this ambassadorial fabric leads to abandonment. In Athens’ case, their allies – angry and slighted – undermined the Athenian cause. From millennia past, the echo of Thucydides rang in my ears. The same risks apply today, when America takes a hardline stance, throwing up tariffs against Canada (its most American-like ally), threatening the European Union (yes, a major beneficiary of American support for nearly a century and philosophically the birthplace of American liberty), and creating so much very public bad will. This public humiliation of allies fosters resentment, anger and, eventually, the cold, hurtful betrayal of friends.

Turning this whole alliance thing over in my head, I realise that I am far from being on my Pat-Malone. The former Four-Star Marine Corps General James Mattis resigned as U.S. Secretary of Defence in December 2018 due to significant policy disagreements with President Trump. In his resignation letter, Mattis emphasised the importance of treating allies with respect and being clear-eyed about adversaries such as Russia and China. He stated that President Trump deserved a defence secretary whose views were better aligned with his own. This resignation highlighted the growing rift between Mattis and President Trump over foreign policy and military strategy, particularly regarding alliances and the role of the U.S. on the global stage. Mattis, a famously well-read warrior, frequently cites Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the Stoic philosopher, as an influence. Different heroes, but we both like old things.

I hope President Trump’s adamant inauguration stance was more theatrical than reflective of reality. However, it does feel as though we are in an Athenian Empire moment. The signs of a hardening American Empire are evident in the unravelling fabric of American society. I have written on this topic previously, and you only need to spend a short time in Los Angeles or New York to see the extent of infrastructure deterioration and feel the white-hot anger of the working poor. America is looking for fault and they seem to be landing on their close friends. There can be no doubt that change is needed – and fast. America, like all nations and people, requires constant reinvigoration. BUT maybe getting the job done with less public anger would be the go. This is a precarious time, and I can’t help but recall Thucydides’ warnings about the dangers of isolationism, imperial anger, exceptionalism, and overreaching when you are without mates.

Michael Reid OAM

Los Angeles Tips

The key to a pleasant – or at least not miserable – experience at LAX is to NEVER use it as a transfer hub. Either fly directly to LA if it’s your destination or route through another city, such as Dallas, to reach New York City. Avoid transiting through LAX, as you must go through immigration, collect your bags, and physically recheck them for a connecting flight. Long lines at immigration often cause significant delays, making missed connections highly likely.

Upon arrival, always pre-book a Blacklane or order an Uber Black for direct terminal pick-up. Regular taxis and UberX rides operate from LAX-it, a chaotic pick-up rank requiring a bus ride from the airport.

Eat

Avalon Hotel, Beverly Hills

9400 West Olympic Boulevard, Beverly Hills, CA 90212

Best poolside burgers.

Dante (Rooftop of the Maybourne Hotel)

225 N Canon Dr, Beverly Hills, CA 90210

Bootleg Taco Stand

225 Lincoln Blvd, Venice, CA 90291

Erewhon (Nowhere spelled backward)

A certified organic grocer. Imagine the best specialist food store and triple it. Multiple locations.

Hauser & Wirth Restaurant / Café

901 E 3rd Street, Los Angeles, CA 90013

Queen Street Raw Bar & Grill

4701 York Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90042

Excellent oysters and chowder.

Hama Sushi

213 Windward Avenue, Venice, CA 90291

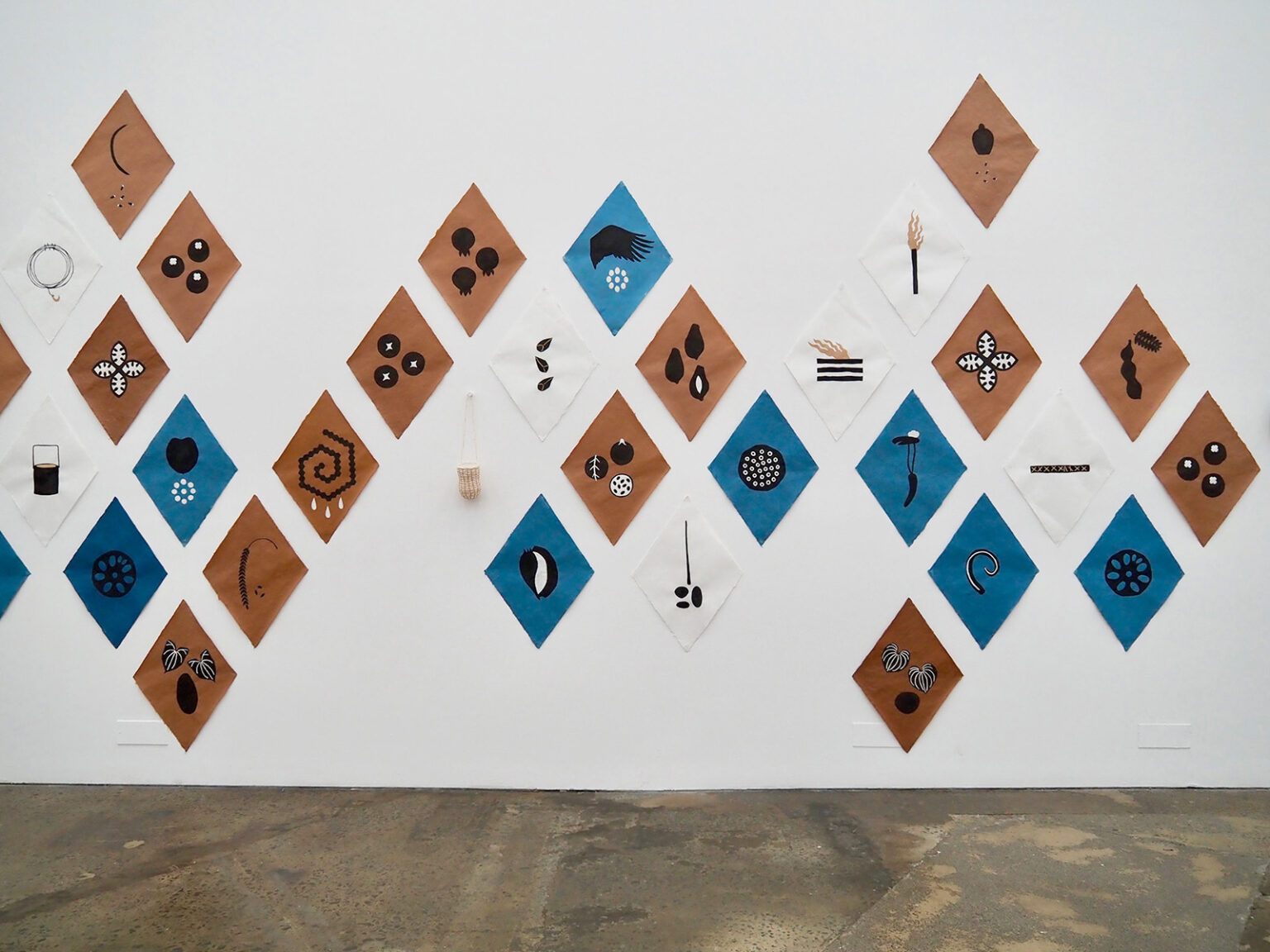

See

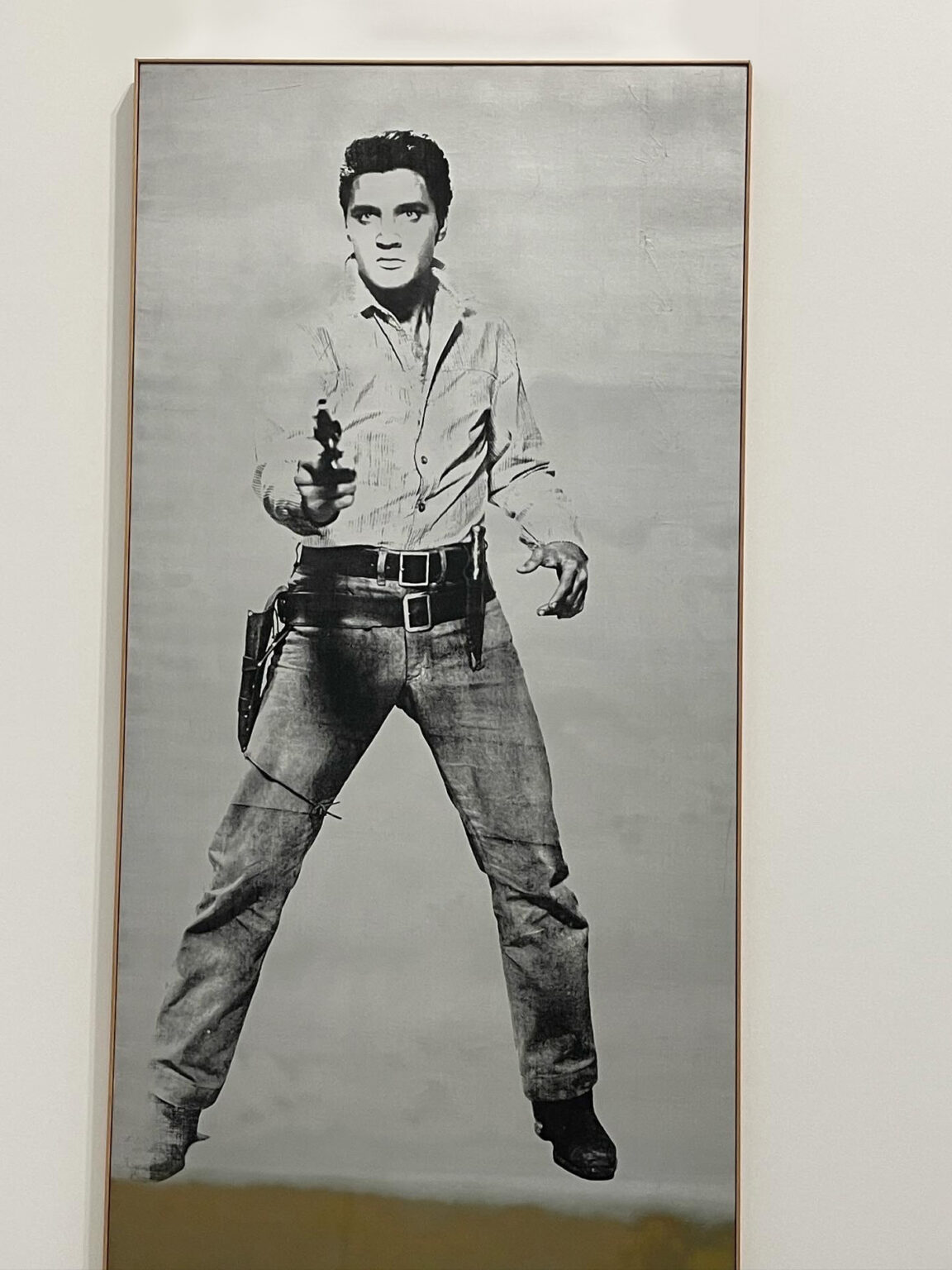

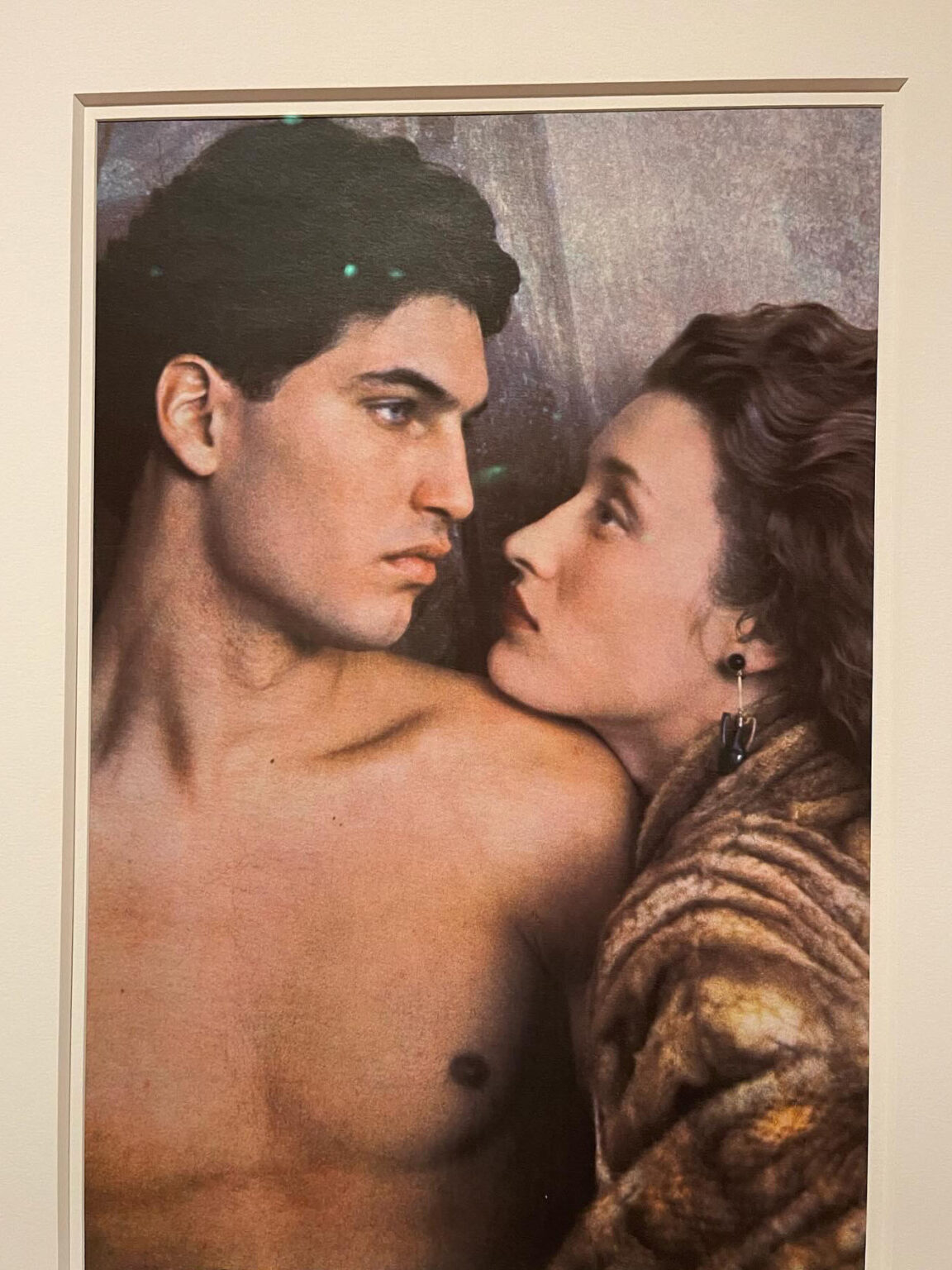

The Broad

221 S Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012

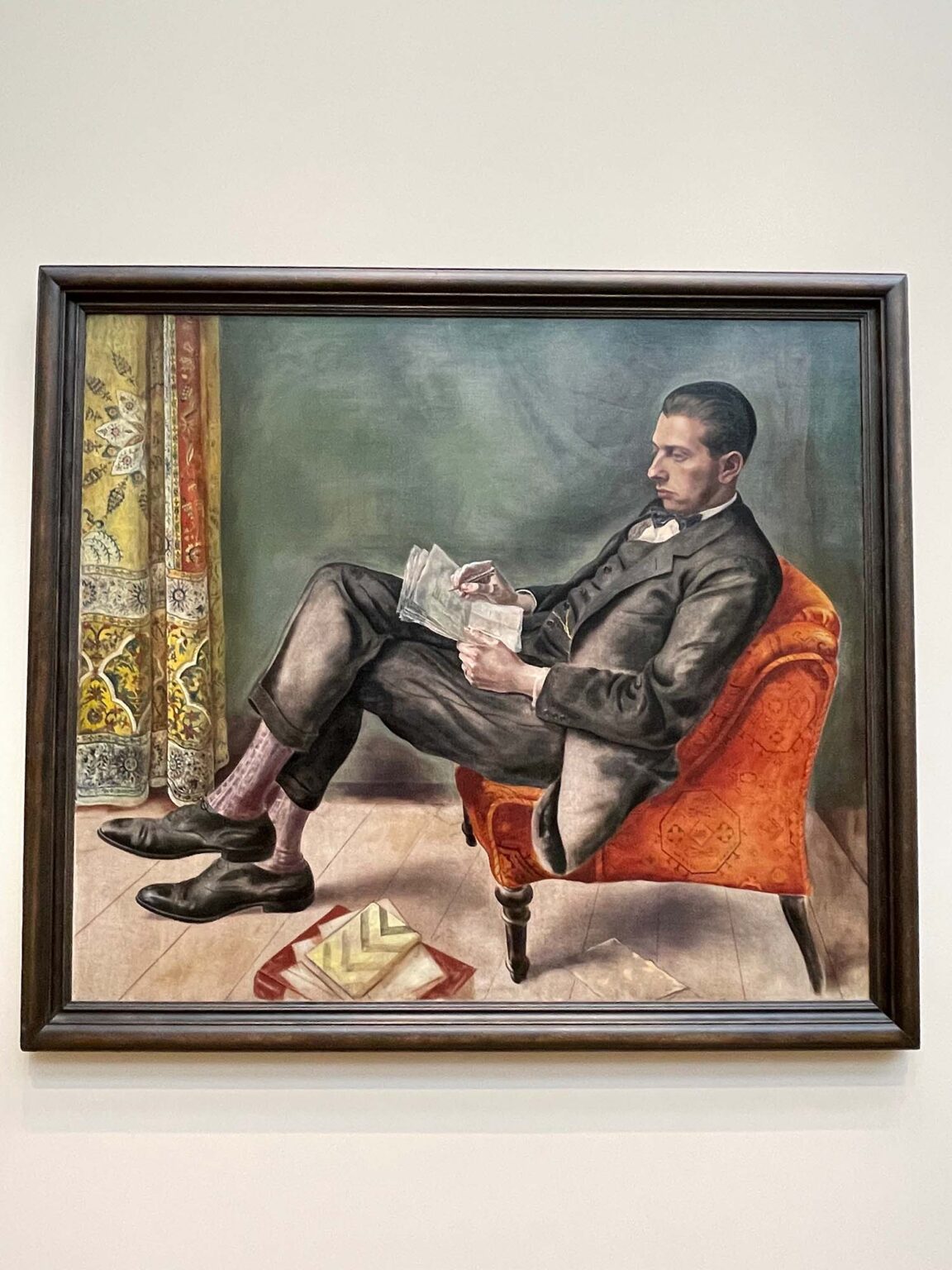

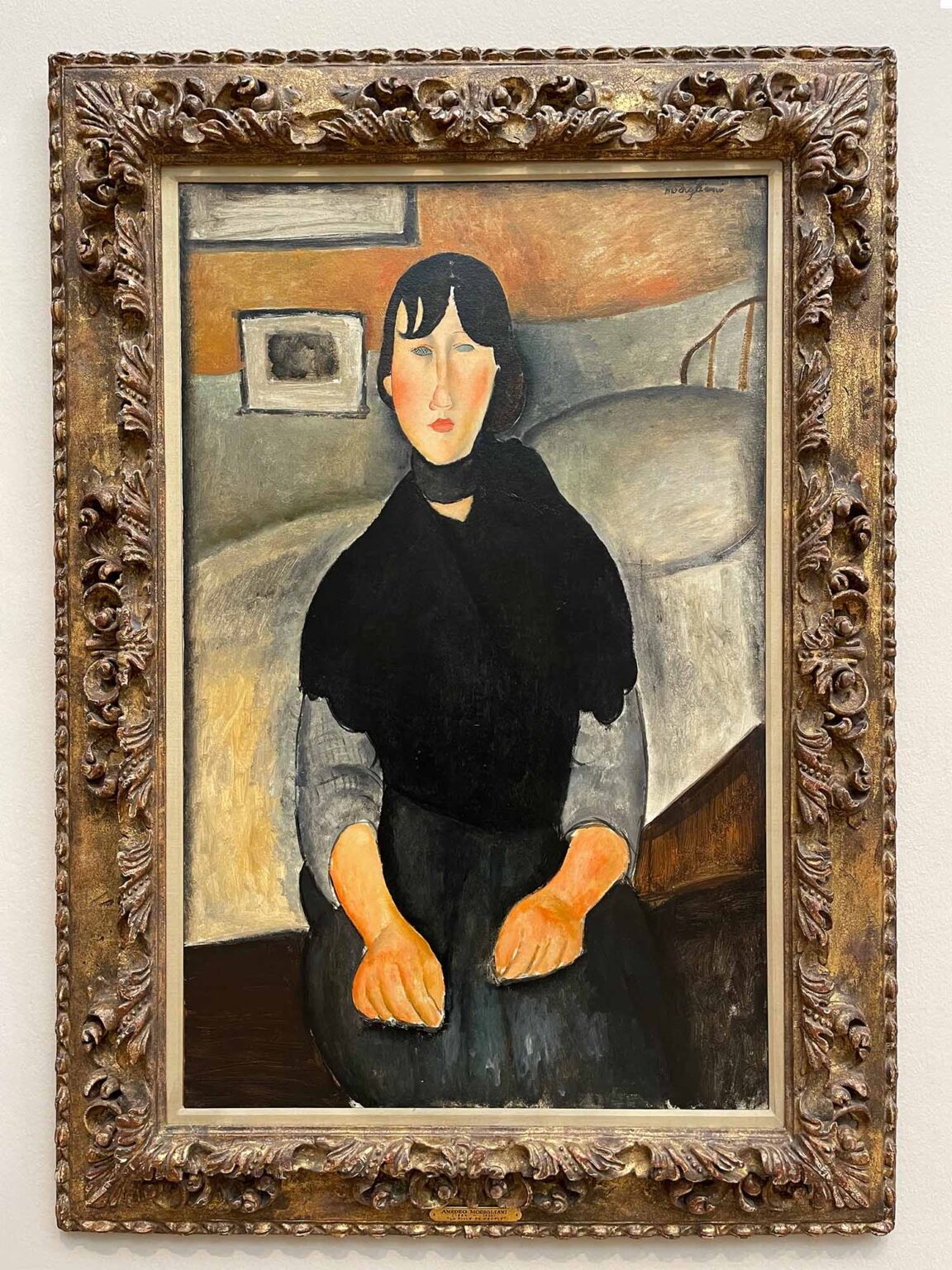

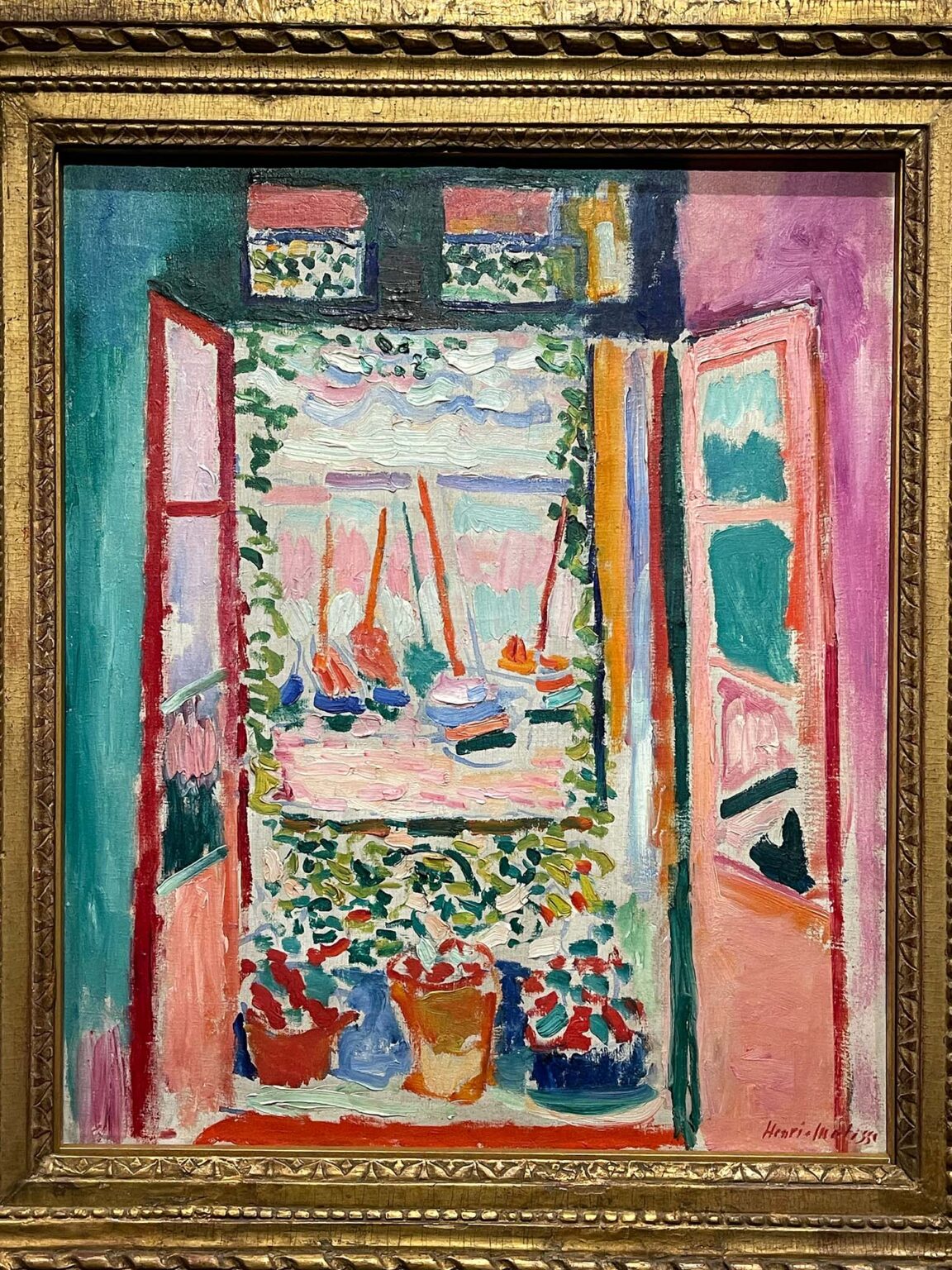

Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

5905 Wilshire Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90036

Architecturally as coherent as a splatter of dog’s vomit, but with one of the most diverse art collections and archives.

The Getty

1200 Getty Centre Drive, Los Angeles, CA 90049

Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA)

250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012

Across the road from The Broad, MOCA feels almost quaint by comparison.

Shop

Dover Street Market

606–608 Imperial Street, Los Angeles, CA 90021

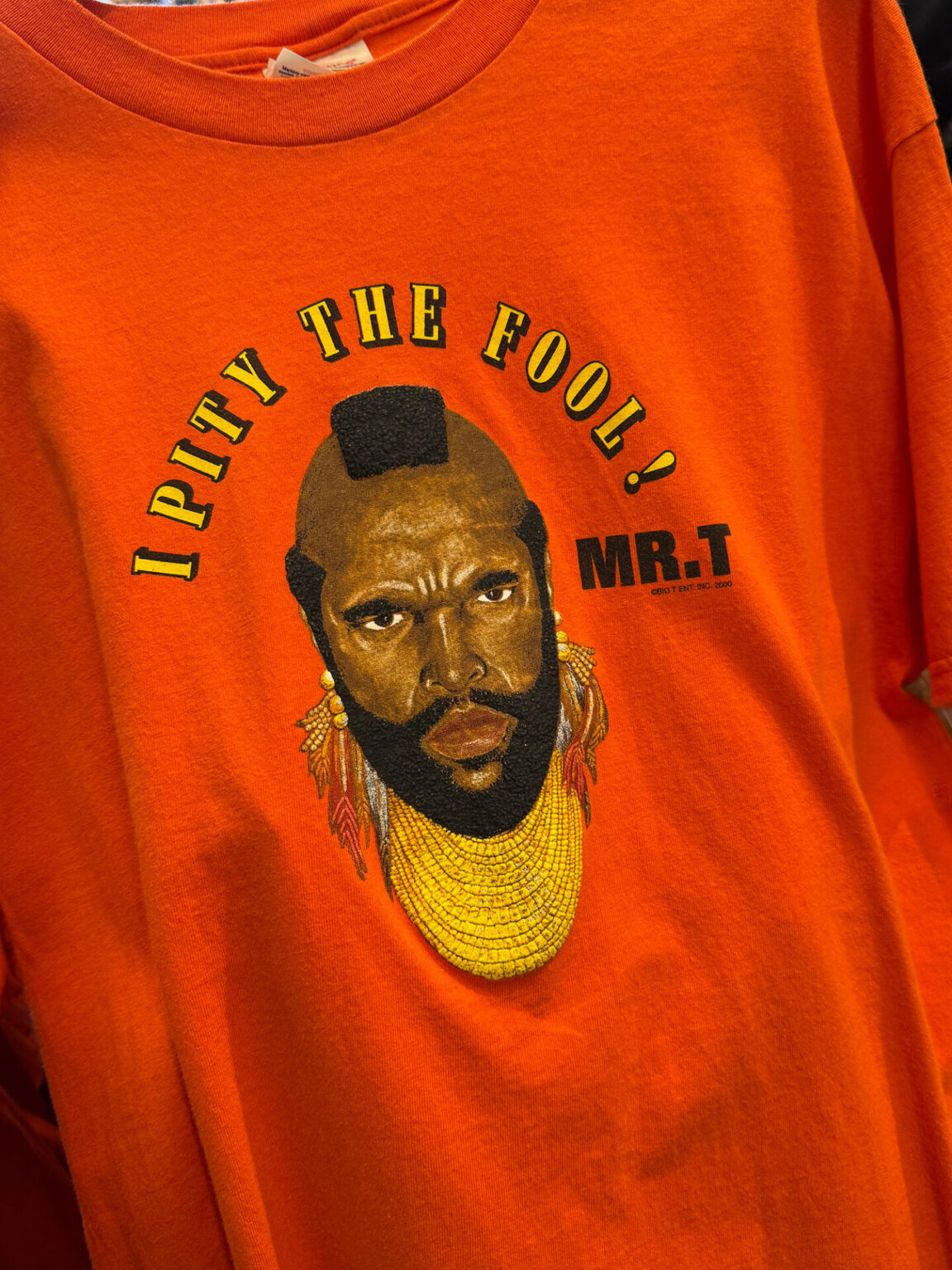

The Bearded Beagle (Vintage)

5820 North Figueroa Street, Los Angeles, CA 90042

Filson (Outdoor Alaskan menswear)

3210 W Sunset Blvd, #1, Los Angeles, CA 90026

Mohawk General Store

4011–4017 W Sunset Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90029

Westfield Century City

10250 Santa Monica Blvd, Los Angeles, CA 90067

Stay

Avalon Hotel, Beverly Hills

9400 West Olympic Boulevard, Beverly Hills, CA 90212