Word & Photography Jason Mowen.

In Australia, the rail scene is a little like gay marriage. Despite our progressive reputation, it took us 17 years to allow same-sex couples to have the full white wedding and the legal recognition that goes with it, after the Netherlands legalised same-sex marriage in 2000. Over that time 24 nations – including historically conservative and religious countries such as Spain in 2005, Portugal and Argentina in 2010 and Ireland in 2015 – signed marriage equality into law, each time shining a light on the fact that we, well, hadn’t.

Similarly, train travel has had its own revolution, at least in the Northern Hemisphere, with the expansion of high-speed rail and the return of the overnight train. The total length of the high-speed network increased globally from 44,000km in 2020 to 59,000km in 2022. At the same time in Europe, the regeneration of, and eco-minded zeal for, cross-border overnight trains has been extraordinary. It’s a great thing (thank you Sweden) as travelling by train emits around six times less greenhouse gases than flying. But despite the Sydney-Melbourne flight corridor being one of the busiest on the planet, in 2023, there is still no plan for high-speed rail between our two most populous cities.

Arguments against flit between “too expensive” and “not enough people” which to me, make about as much sense as that one against gay marriage: that next we’d want to marry our pets. I’ll draw again on the Iberian example. When Spain launched the AVE high speed rail service between Madrid, Cordoba and Seville in 1992, the combined population of those cities amounted to 5.4 million people. The population of Sydney, Melbourne and Canberra, meanwhile, is already approaching 11 million.

So is there another, less tangible layer to this ongoing resistance to rail and if so, does it have something to do with our own class constructs surrounding train travel? For example – referring to Spain one last time – I had a Sydney friend come to visit me when I lived in Madrid. She planned to travel around the country and was mortified when I suggested she take trains, which she considered too downmarket a mode of transport. She proceeded to explore Spain by bus – madness considering the breadth of the Spanish rail network where even aristocrats don’t turn their nose up at catching the odd train. Hopefully, though, much like gay marriage, we’ll get there in the end. Beyond the environmental benefit there is still nothing as romantic as travelling by train, which even at its most basic offers the simple luxury of slowing down and watching the world go by. And we are, after all, already home to one of the most legendary trains on the planet: The Ghan.

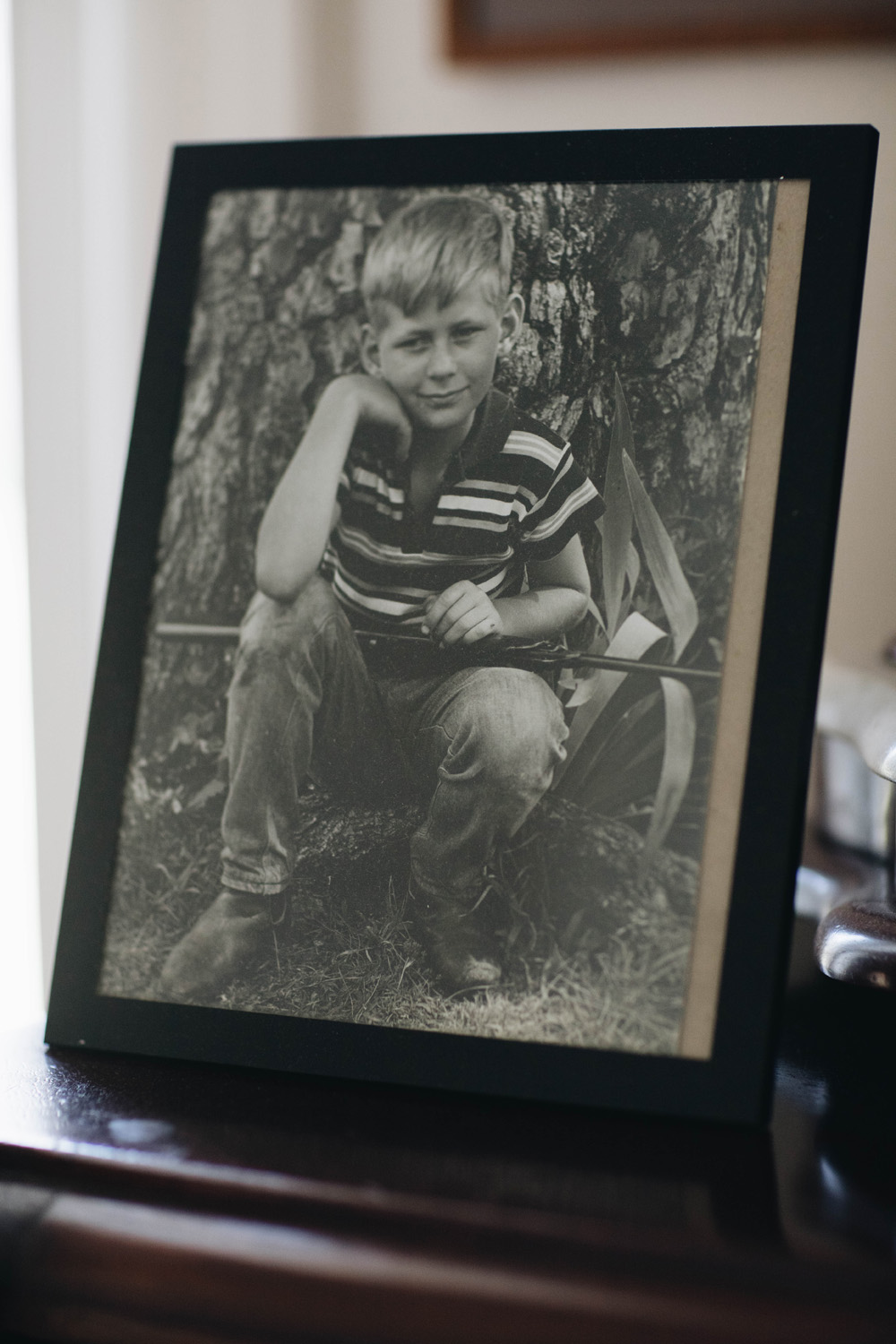

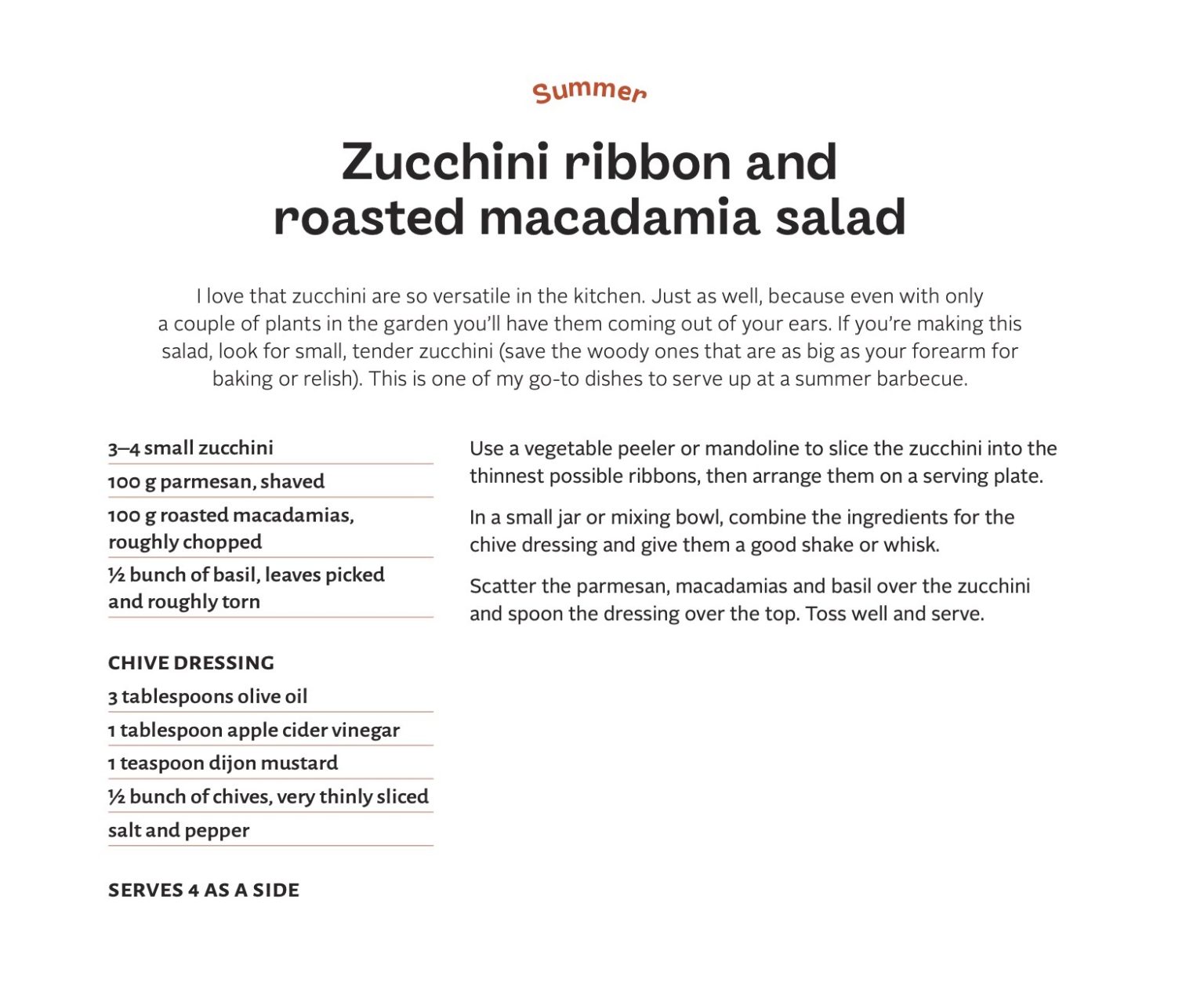

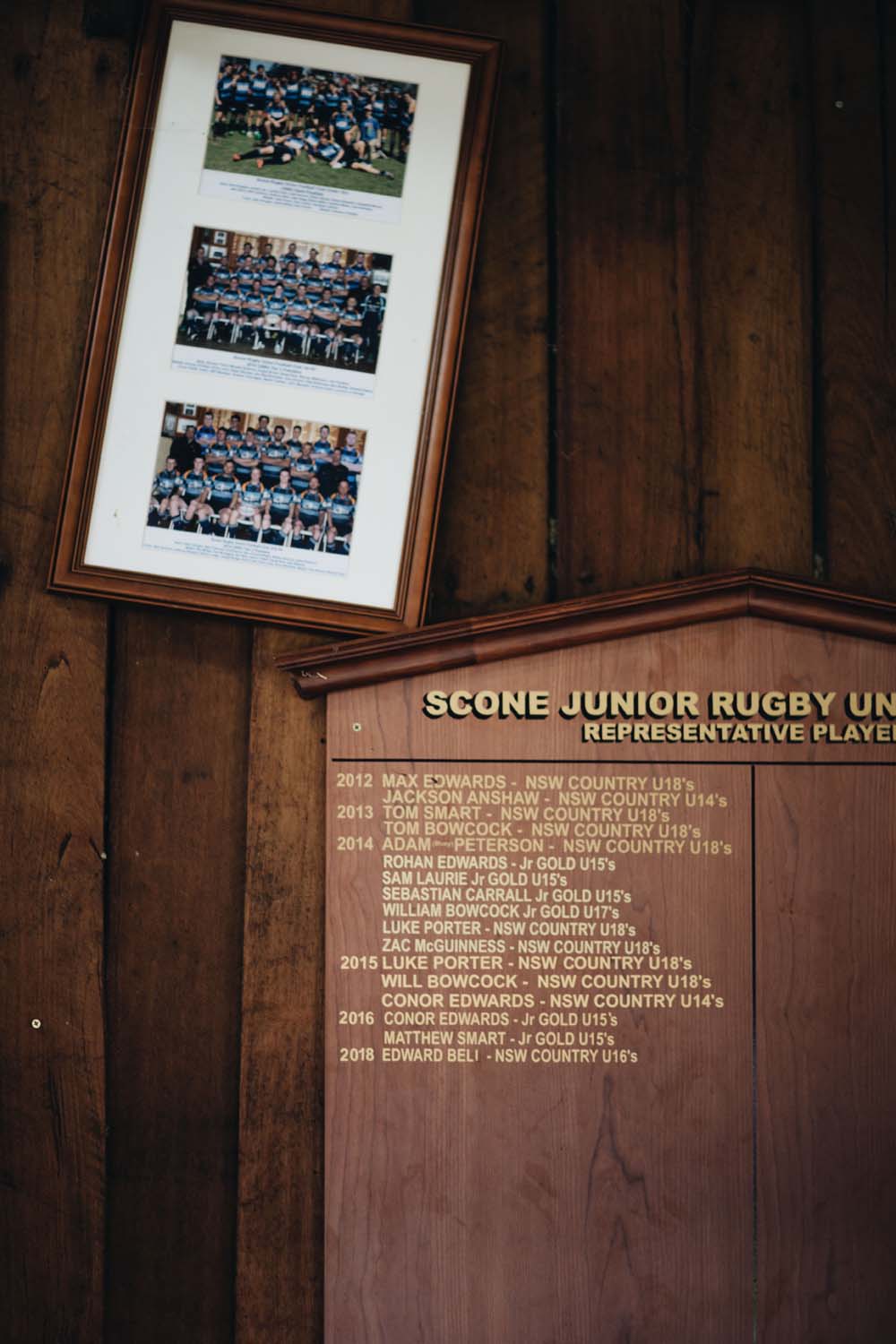

Everything about The Ghan – which I had the great pleasure of travelling on, Darwin to Adelaide, in March – is epic. Two NR class locomotives tow 265 passengers a distance of 2979 km in 38 carriages, cutting through the red centre of the driest inhabited continent on earth in just over 53 hours. Just as epic is the story of the line’s construction, 126 years in the making, breaking ground in Port Augusta in South Australia in 1878, reaching Alice Springs in 1929 and not making it to Darwin, as had long been intended, until 2004. Even the train’s name is wrapped in legend, referencing the Afghan camel drivers who came to Australia in the 19th century to help the British forge a path to the country’s interior. As a result it should probably be The Ghan (as in man) rather than The Ghan (as in barn) although the full gamut of pronunciation is heard up and down the 901-metre-long train.

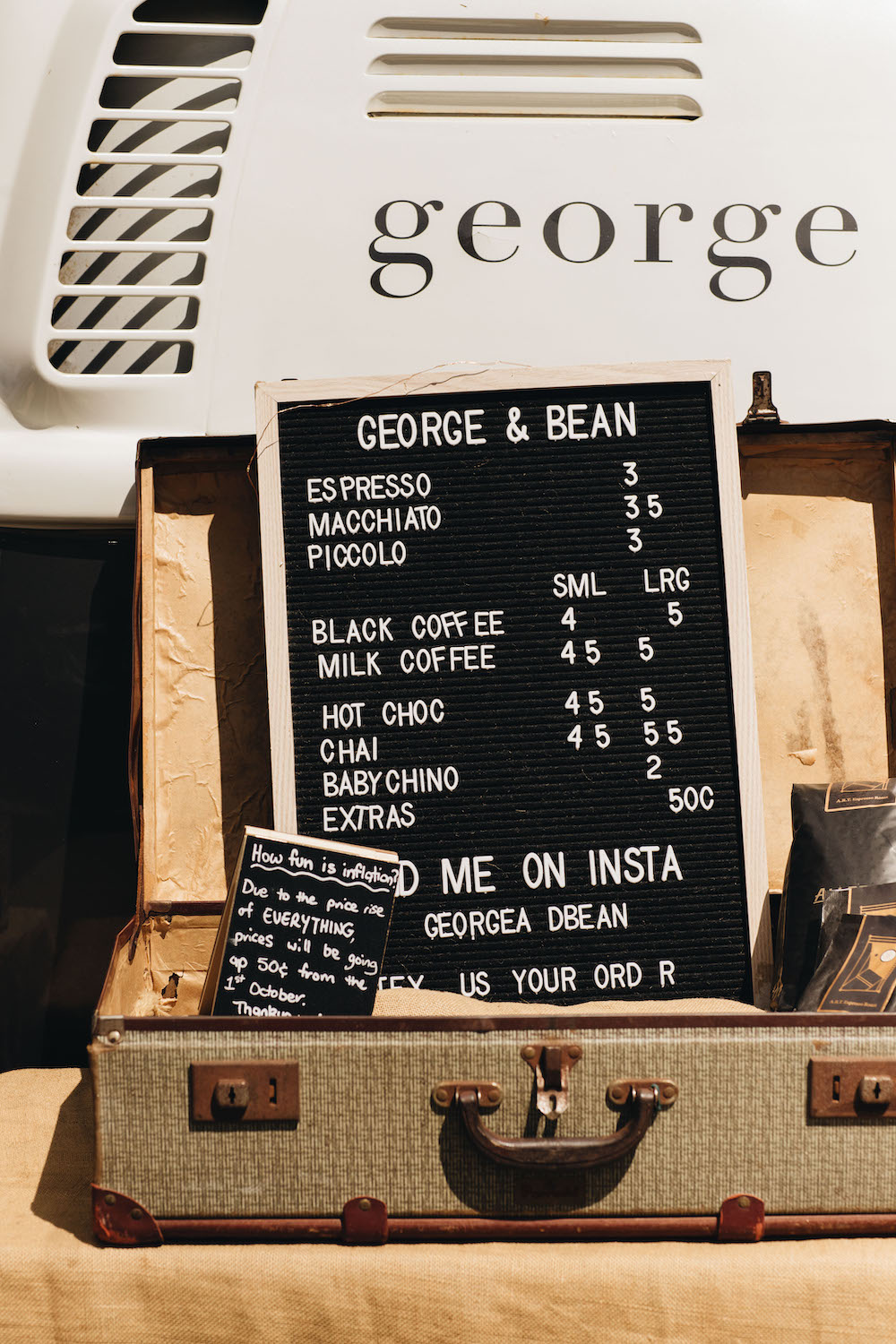

My trip began at the swank Hilton Darwin where Journey Beyond, The Ghan’s operator, does check-in before whisking passengers to Darwin Berrimah Rail Terminal for the 9.30am departure. The Hilton, a late Brutalist pile in the centre of town with just-renovated public spaces, features a slick lobby bar, the elegant and award-winning PepperBerry restaurant and a 12th-floor executive lounge, where boucle-covered tub chairs face picture windows with sensational views over the Timor Sea. I got the first sight of my fellow passengers in the lobby the following morning, an older crowd with a smattering of twenty- and thirty-somethings being checked in by Akubra-wearing hospitality assistants.

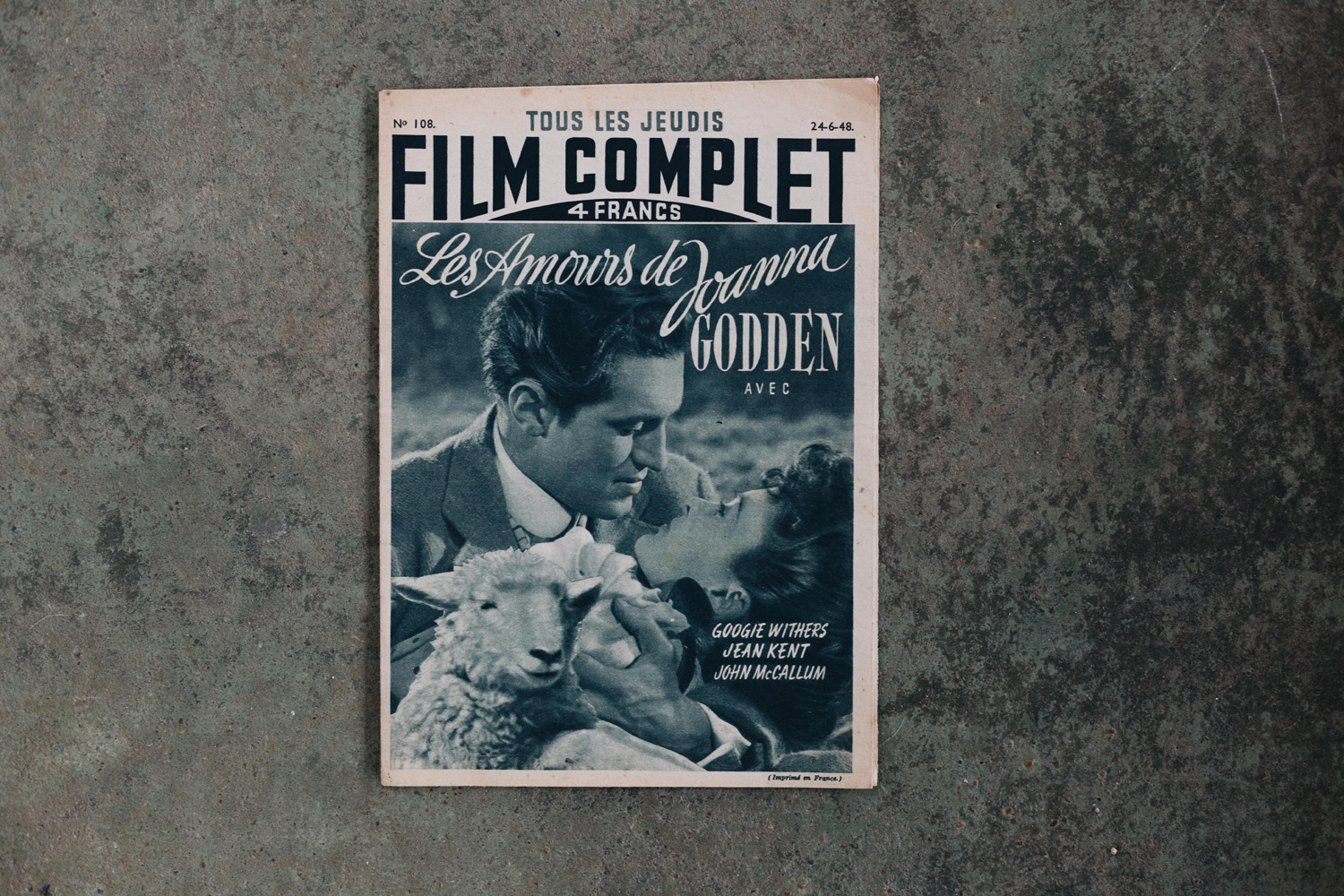

In my solo-travel loving mind, the journey was going to be a three-day meditation broken only by daily forays into the desert and trips to the dining car where I would eat on my own and observe, Poirot-like, my fellow passengers. I’d explore the train and have a drink in the lounge car, passing the rest of the time in my compartment, a little reading, a little writing and lots of getting lost in the mesmerizingly beautiful landscape whizzing by. I think of Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint when it finally comes time to board – Nostalgia when travelling is like a drug – the retro lines of the silver carriages recalling North by Northwest.

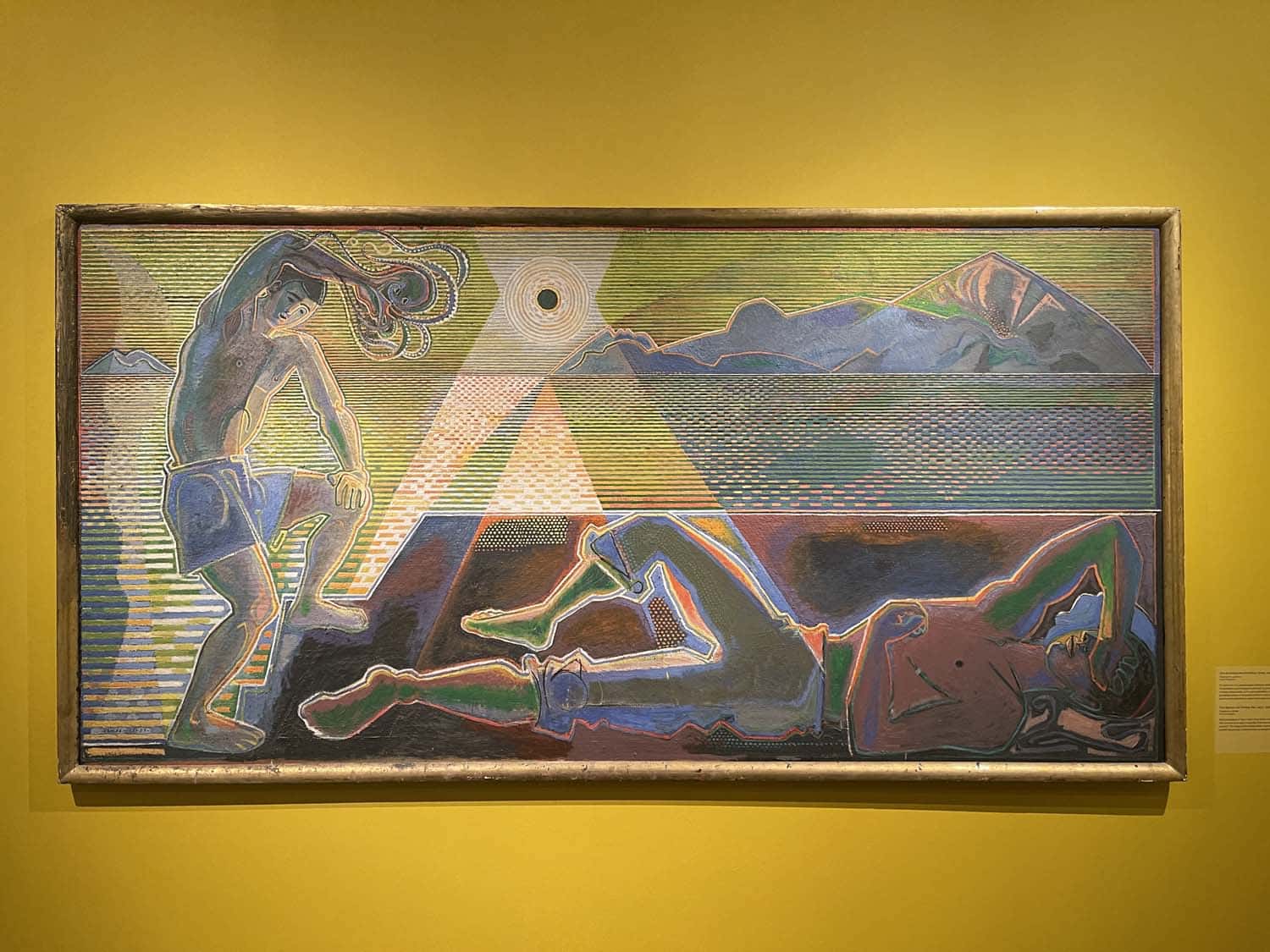

Hospitality assistant Bethany shows me to my compartment, a Gold Service Twin, which features a three-seat “day lounge” that converts to upper and lower sleeping berths at night, a small table, wardrobe, safe and various storage compartments. There’s a radio with music channels, a large double-glazed window with enclosed venetian blind – great for controlling the desert light – and a compact ensuite with shower, basin and loo, fluffy white towels and bathroom products from Appelles Apothecary. The interior has some age to it but is well maintained and proves abundantly comfortable over the coming days. In either case Woods Bagot, the Adelaide-based architects behind the 2019 refurbishment of the train’s sumptuous Platinum Service carriages, are about to work their magic across Gold Service. Architectural renderings depict sleek and sophisticated spaces in a subtle palette inspired by the landscape paintings of Albert Namatjira.

The next 53 hours fly by like a dream, although not quite the one I had in mind. I receive my meal card from Bethany and learn that not only must we eat at very specific times but four to a table, elbow to elbow with strangers, my Hercule-Poirot fantasy of quaffing claret after dinner as I jot down brilliant ideas in a notebook evaporating into the night. But this is where The Ghan gets interesting. The camaraderie, sharing meals, tales, and desert expeditions with such a broad cross section of passengers is ultimately what makes the journey so unforgettable.

Deciding to jump right in, I head to the Outback Explorer Lounge where spirits are high and the spritzes and mimosas are flowing – Croser in Gold Service and Bollinger in Platinum – despite the fact it’s not quite 11am. A British woman, cappuccino in hand, just manages to fall into the last available place on the banquette opposite me as the train takes a sharp corner. We strike up a conversation: Susannah is a business consultant and executive coach from Essex, in Australia to see her daughter who lives in Perth, and travelling solo on The Ghan to give her son-in-law some space. I liked her immediately. We are soon joined by Emanuele, a super charming Italian who lives and works in Singapore and moonlights as a travel and wildlife photographer, and his lovely mother Mercedes, from Ancona. Mercedes doesn’t speak English but the four of us find our rhythm, reconnecting between meals and excursions over the coming days.

The Ghan is renowned for splendid food and wine so it was with excitement that we made our way to the dining car, one carriage back. The Queen Adelaide Restaurant takes its name from the consort of William IV, the king of England when South Australia was settled in 1836. I’m seated with Len and Diane from Caboolture – Len used to drive trucks across the Nullarbor – and Pat, a radiologist from Yorkshire, full of stories from her time living and working in the outback in her twenties. The two-course lunch offered a choice of three mains, two desserts and an impressive lineup of 13 Australian wines by the glass, including a Clare Valley sangiovese rose that paired perfectly with the Massaman Buffalo Curry. Over coffee, Pat produced old Australian banknotes that her parents had given her in 1980, the orange and yellow of the $20 bills as bright as ever.

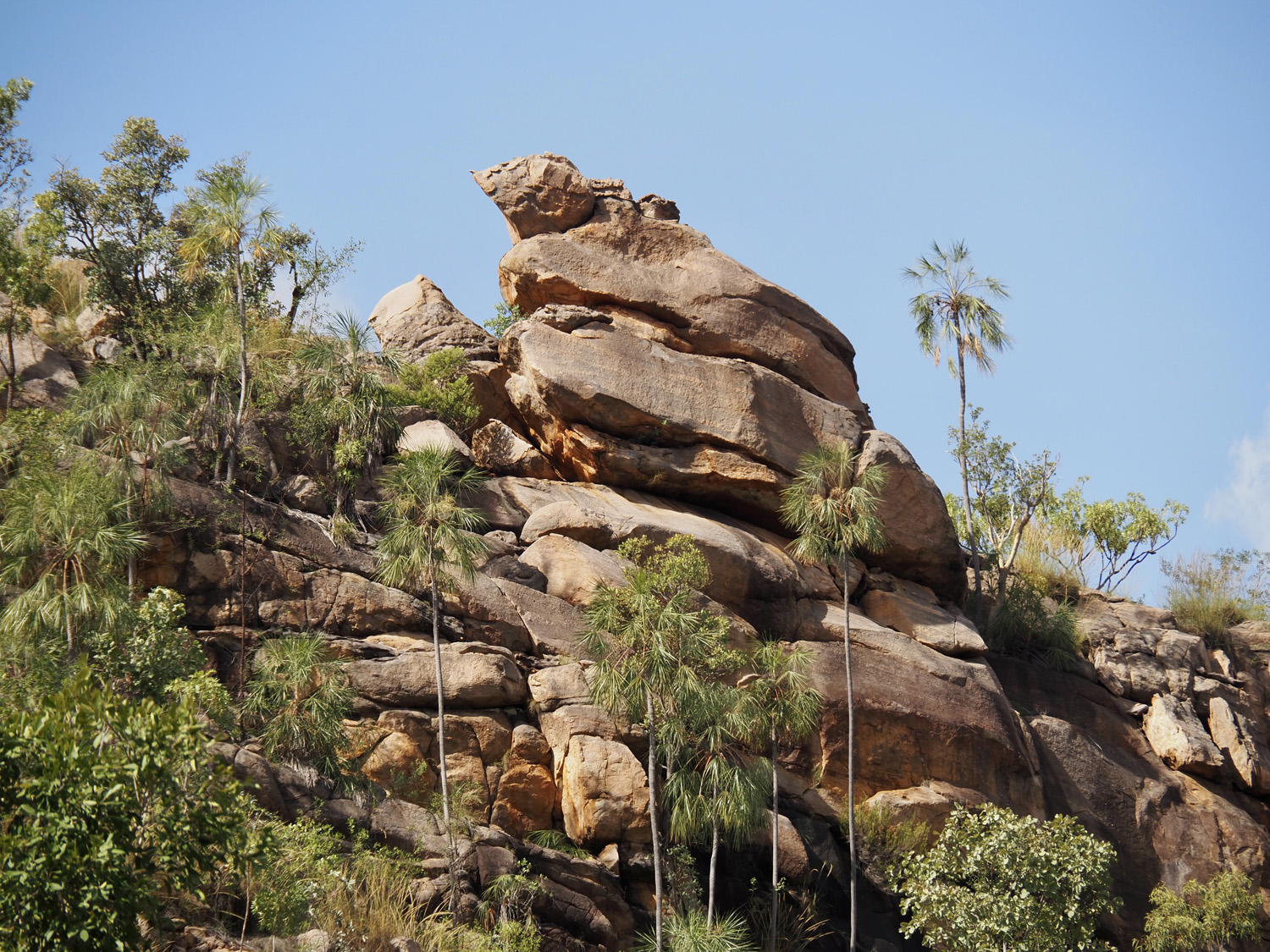

For off-train experiences, I went for the Nitmiluk Gorge cruise on day one, near Katherine, and the Simpsons Gap discovery walk on day two, just outside of Alice Springs. Both were astoundingly magical. The 38-degree heat and coach-tour aspect of getting 265 people out and back in three hours is at first, to someone who has never taken a tour, a little confronting. Then you’re face to face with the wild majesty of these jewels of the outback and all is forgotten, a little like looking up to the sky on a clear night and realising how small we are. We learnt on the cruise, for example, that the sandstone forming the gorge is 1.6 billion years old. Our captain-guide hailed from the Jawoyn people and lulled us into an almost hypnotic state with his beautiful voice, smooth boat skills and tales of the rainbow serpent.

On the final leg I sat next to Breena, a young solo traveller from Maryland, who spoke to me of her love of cloud formations and the minutiae of nature. I dined with a New Zealand couple that evening – three courses including delicious saltwater barramundi – making a dint in the wine list as we discussed Antipodean adventures. We met Susannah and Emanuele for a nightcap and a lot of laughter in the Outback Explorer Lounge and finally, falling into the bed that Bethany had made up while we were at dinner, lights dimmed and a chocolate on the pillow, I dozed off with a smile on my face

Day two was a cracker. I met Amanda and David, a lovely couple from Perth, at breakfast, comparing notes on our first night’s sleep and downing good, strong coffee as we pulled into Alice Springs for the next adventure. It was a much smaller group for the Simpsons Gap expedition, which I was happy to see included Breena, Susannah and Emanuele. I’ve seen beautiful desert landscapes before – North Africa, Jordan, Arizona – but the West MacDonnell Range was something else, vast and raw. Ghost gums punctuate the landscape – a Fred Williams painting brought to life – along the approach to the soaring pass, the contrast between blue sky and red rock dazzling. The area is an important spiritual site to the Arrente people, as several dreaming trails and stories cross here and even to first-time visitors, Simpsons Gap was a large and moving experience that led to even more meaningful exchanges back on the train.

Showered, changed and ravenous after the adventure, I made my way to the dining car where Pat and I had lunch with two of the most amazing women I’ve ever met. Shirley and Sandy are school chums from Townsville at the upper end of The Ghan’s age spectrum, who haven’t seen each other in years. Shirley now lives by the bay in Melbourne while Sandy is raising her two grandchildren in Townsville, where she has an Albert Namatjira tucked away in a wardrobe for safekeeping and still works as a nurse. She lived in London in the “swinging” sixties where she worked as a midwife and bought, with four other midwives, an old London black cab they then drove across the continent to Greece. Shirley, meanwhile, wanted to be an architect. When her father stopped her, telling her it was no career for a young lady, she rebelled with martial arts, earning a blue belt in judo and a black belt in jiu-jitsu. All three had just done the tour of Alice Springs and the contentious subject of the town’s Indigenous youth came up, as it had many times on the train. What was touching, though, was to hear women of their vintage discuss the subject with such empathy and generosity. It filled me with hope, a perfect end to the perfect lunch.

Susannah and I caught up in the lounge where we talked about love, life and the surprising contentment of flying solo in the world, sure in my mind at the time that I’d found my long lost twin. Emanuele arrived and we ordered spritzes; and then Mercedes with a board game none of us had heard of. Her appeals to the crowd for instruction in Italian were hilarious and eventually we are joined by Julie, who knows the game. We somehow get through a round, Mercedes asking questions in Italian, Julie with the thickest Aussie accent enjoying her first spritz and Susannah and I giggling away.

After dinner, the train stopped in the desert where a massive bonfire had been set up for us, not too far from the tracks. I couldn’t find the crew from that afternoon but ran into Amanda. We were both tired – it had been a massive couple of days – and after several minutes of silence looking up to the stars, she opened up to me about life and loss and her recent interest in meditation. I had just returned to my own meditation practice so wonderful timing, two strangers discussing the largeness of life, under the most magical sky.

I’d noticed a German couple on the Simpsons Gap walk and was delighted to find them at my table for brunch the following morning, untimed and leisurely as there was no off-train activity before arrival into Adelaide that afternoon. They’d been living in Vietnam for many years and were travelling through Australia before returning to Europe to start a new life in Vienna. I love Germans: their frankness, their politeness and their accent speaking English. We discussed Indigenous culture and the current tensions in Australian society, as well as their lives growing up in East Germany. They considered themselves to have been incredibly fortunate, completing their state-sponsored tertiary education just before the wall came down, and all of the freedom and opportunity that followed.

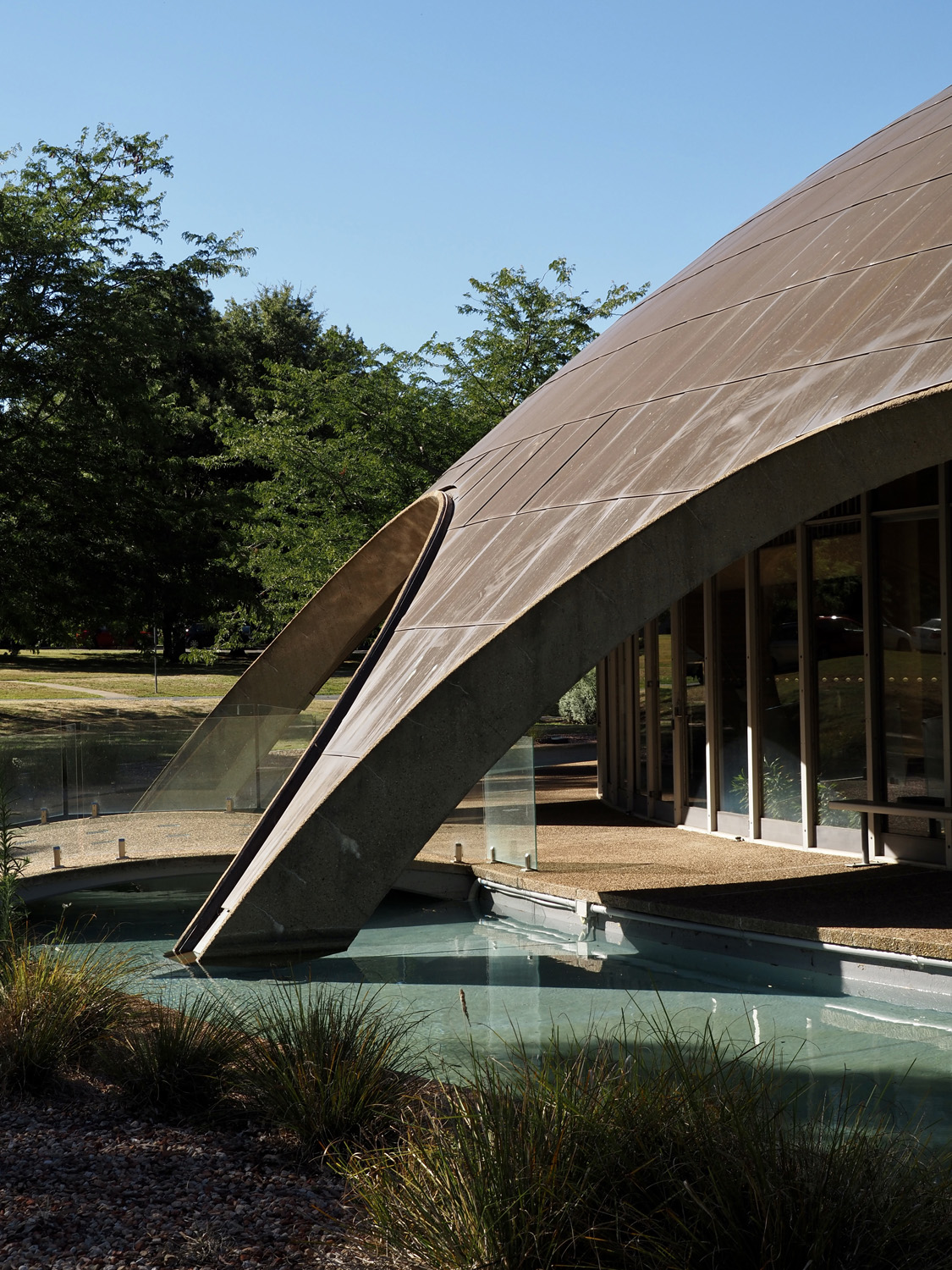

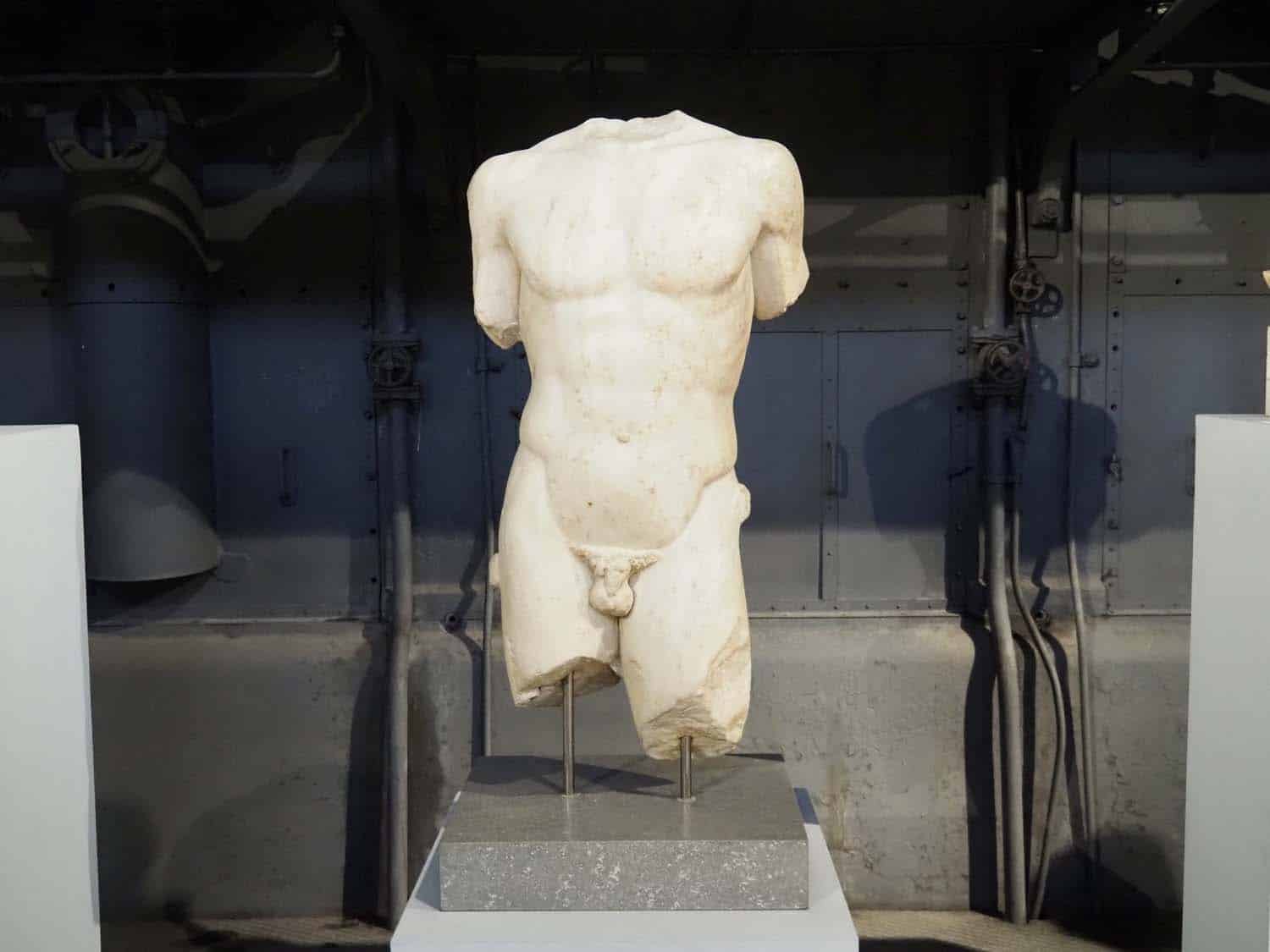

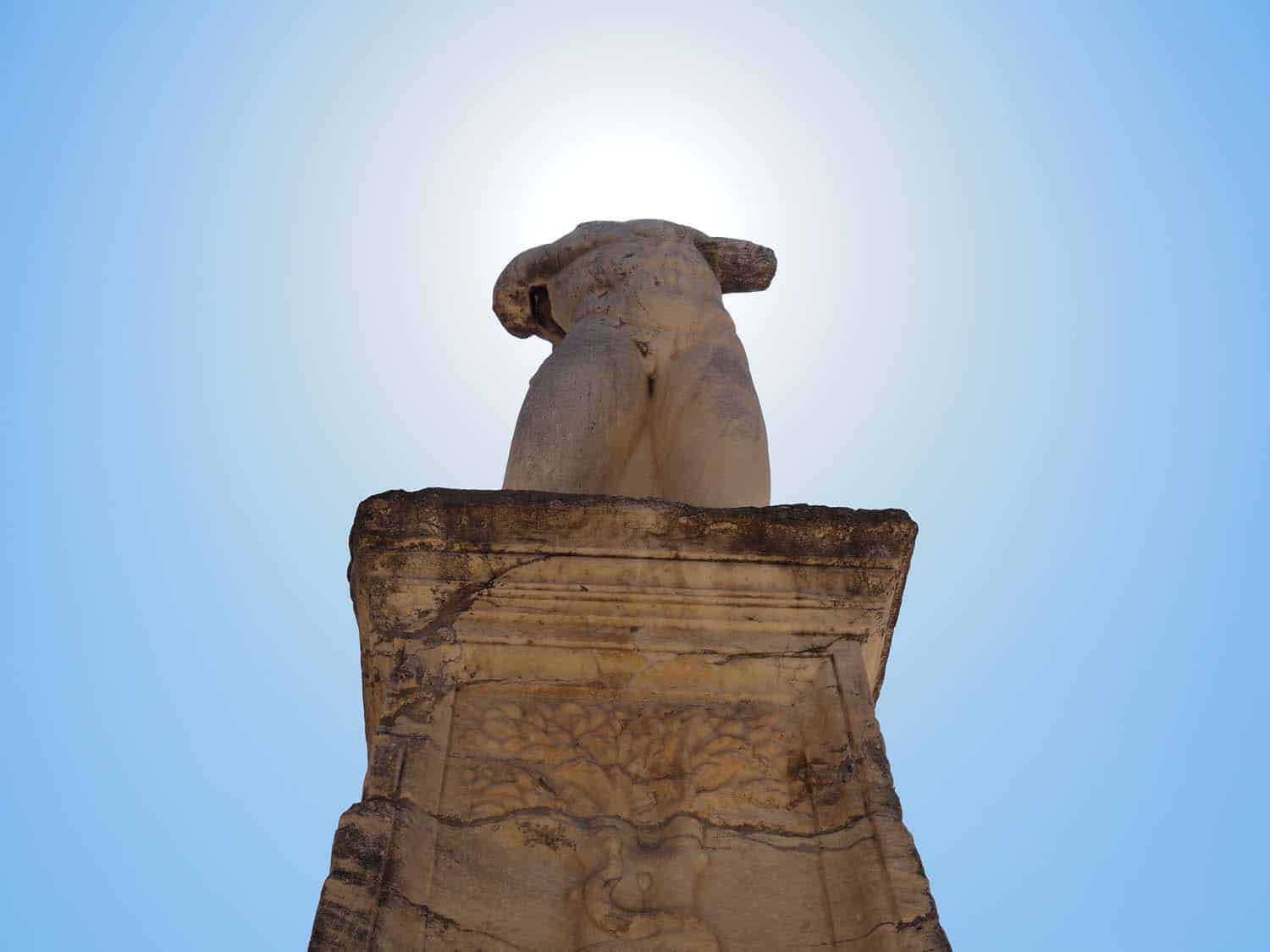

In what seemed like a flash, we were pulling into the station, the journey completed, promising to stay in touch. That would be my only criticism of The Ghan: like the most amazing dream it is over too quickly. But I was also excited to be in Adelaide for the first time and staying at Eos by Skycity, a dazzling beauty of a boutique hotel perched on a picturesque bend in the River Torrens. A temple of contemporary understatement, Eos takes its name from the Greek goddess of the dawn, breathtaking views of which can be seen through the hotel’s curved walls of glass. Having less than 24 hours to get a sense of the city, I was thrilled to see so much of it from my room: clean, green and with pretty architecture, stretching all the way to the Adelaide Hills.

I made my way to the Art Gallery of South Australia, just a few blocks from Eos. What a museum: small but packing enormous punch not only in the calibre of the collection but in the fascinating way each space is arranged. It has the intimacy of a really good house museum – John Soane meets Kettle’s Yard meets Antwerp modern – but some grandeur too, with dollops of Australiana and marvellous Indigenous art. The city has its Friday night buzz on as I head to newcomer eatery, Fugazzi, perching myself at the low-lit bar to savour what was possibly the world’s most delicious gimlet – the cocktail onion pickled in balsamic – alongside a prawn and white pepper mayo roll and yummy maccheroni with anchovy, chilli and pangrattato. It had been a whirlwind few days and I was finally alone, still smiling but already missing my friends from the train.