Tamara Dean, one of Australia’s most acclaimed photo media artists, has taken her focus on the human connection with our environment, and her fascination with the other-worldly qualities of working in water, to a new level by building an underwater studio on her property near Kangaroo Valley.

The first works from the studio will premiere in Palace of Dreams, her exhibition at Sydney Contemporary.

For as long as she can remember, Tamara Dean has felt close to nature. As a child growing up near Lane Cove National Park, she loved the bush and through her teenage years she would explore and sketch obsessively at every opportunity.

Her family used to visit Kangaroo Valley during school holidays and she also went to school camps at Chakola, which had been established near Kangaroo Valley in 1965 to offer “creative leisure” and “experiential learning” for school-aged children. Toward the end of her high school years, she also worked at Chakola.

“It was the first piece of land that I felt I really knew, and it really stuck with me,” Dean recalls. She now lives just 15 minutes from Kangaroo Valley and her love of nature continues to inform her life – and her art.

This story is our August feature on the Southern Highlands publication ‘The Scrutineer‘, based out of our Berrima gallery, Michael Reid Southern Highlands.

A recurrent theme in Dean’s work is that humans are inextricably part of nature, but nature is increasingly fragile and we are dangerously distracted from recognising this truth. She aims to remind us that we are neither separate from, nor superior to, nature.

When she released her Endangered series in 2019, she described it as “reframing the notion of ourselves as human beings – mammals in a sensitive ecosystem, as vulnerable to the same forces of climate change as every other living creature.”

Endangered featured stunning images of naked women and men swimming underwater in a variety of formations, like shoals of special sea creatures. The series was shot in Jervis Bay in cold and difficult conditions – and was a huge success.

Despite this achievement, Dean realised she had only touched the surface of what might be achieved with submarine subjects.“When I shot Endangered, I discovered that working with underwater cameras was very clunky,” she says. “I didn’t have enough control and it was very frustrating. So I started thinking about an underwater studio, or something that I could use as one – even someone who was willing to let me use their pool. But I couldn’t find anything suitable, so in the end I decided I would build something myself.”

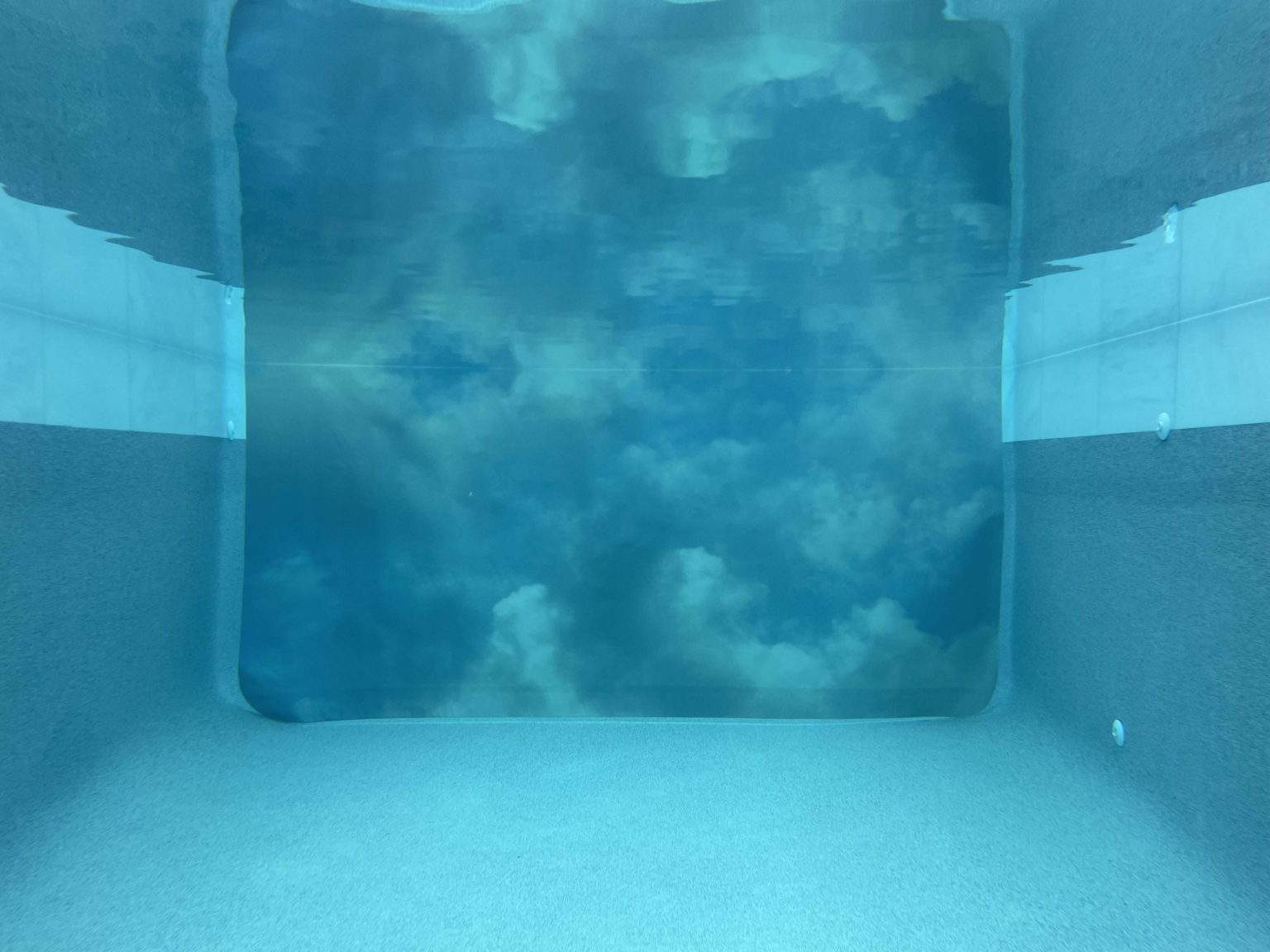

What Tamara built, working closely with Travis Lamb of Lambuild, is an off-form concrete underwater studio that is 12 metres long, four metres wide and two metres at the deep end. The viewing window is three metres wide, one metre high and made of acrylic glass to achieve the best image clarity. It incorporates a Naked Pools freshwater system that uses copper and silver instead of harmful chemicals to filter and sanitise the water while preventing algae growth. It’s the same technology used by NASA to purify drinking water. There is a heating system that warms the water to make it more comfortable during longer shoots – an important consideration in a Cambewarra winter.

“The studio has been specifically built so I can photograph from the outside and use sets inside if I want to, as well as a range of lighting effects,” Dean says. “It allows me to use better photographic equipment than when I shot Endangered. I have more control and, importantly, it gives me a lot of flexibility. It also means I don’t need to get wet!”

So what is it about underwater photography that appeals to Dean?

“I aim for an other-worldly quality in my work and I really enjoy the sense of semi-abstraction and of tampering with gravity that happens in underwater spaces,” she says.

“Working in water also helps me to express my deep concerns about the environment and bring that conversation to my work. Humans are as vulnerable to the forces of climate change as every other living creature, as we can see from the impact of rising tides and the lives lost in the recent floods. Water is even a factor during bushfires, with people evacuating to beaches and seeking refuge there.”

Building the pool has been a “deeply frustrating” process for Dean. It was scheduled to be finished by the end of 2021 but the extraordinary rains along the east coast of Australia meant this deadline could not be achieved. “Then every second tradesperson we were using either got COVID or had to isolate,” she says.But now her “crazy venture” is complete, and so is the body of work that constitutes Palace of Dreams.

“The new studio allowed me to turn images on their axis and show the discombobulating sense of defying gravity. I can create a dream-like world, this other reality with people appearing to be swimming and flying at the same time. I can get a beautiful sense of flow through the hair and the figures, almost a dancing motion.”

The title of the exhibition is drawn from Alice Through The Looking Glass (The Mad Hatter tells Alice: “In the gardens of memory, in the palace of dreams, that is where you and I shall meet.”) and so are the titles of a number of the new works.

“I’m playing into the idea of a world turned upside down and I am weaving in topics such as climate change and rising sea levels without being too dogmatic. I aim to touch on the environmental concerns that I have while delving into the psychological responses that are so prevalent. The feeling that our future feels uncertain, the idea of where is up and where is down?

“It was only at the end, when the works had come what they’d become, that I had the ability to see the literary references I could make. They related to the dream-like, surreal nature of the imagery.”

Palace of Dreams will show at Carriageworks as part of Sydney Contemporary from 8 to 11 September.

Tamara Dean’s career achievements include being commissioned in 2018 to create In Our Nature that was presented at the Museum of Economic Botany (Adelaide Botanic Garden) for the Adelaide Biennale. She has been awarded the Goulburn Art Prize (2020); Moran Contemporary Photographic Prize (2019); Josephine Ulrick & Win Schubert Photography Award (2018); Meroogal Women’s Art Prize (2018); and the Olive Cotton Award (2011). Her work has been acquired by the National Gallery of Australia; Parliament House Art Collection, Canberra; Art Gallery of South Australia; Mordant Family Collection Australia; Artbank Australia; Balnaves Collection Australia; and Francis J Greenburger Collection (New York).